The climax of my movie journalism occurred after the turn of the century. For six years, I worked as a partner, writer and editor for Box Office Mojo, a movie website, which no longer resembles Brandon Gray’s original website, which he founded as a box office tracking source (it evolved upon my 2002 contracting as an editorial operation). I was added to write reviews. My role expanded to cover movie theme parks and film franchises, interviews, a weekly column and editing articles, including box office reports, as well as creating themed pages, features and pictorials.

My movies reporting originates, however, with two 1993 films I reviewed when they were later released on home video; Swing Kids and Rudy. Both are emotionally powerful movies by my judgment. Both received sincere and passionate reviews by yours truly. By then, I was writing news, opinion, sports and features—i.e., articles about people, books, radio, interviews, broadcasting, arts and music—and other journalism.

Among readers, my movie writing gained favor, praise and attention more than other categories. I don’t think this is entirely by my own doing. By the 1990s, Western culture had markedly dumbed down—it’s been going down for decades—with general audience attention and focus driven by prevailing trends, trivia and perceptual material, such as pictures (later memes and emoticons), and phrases, not concepts or ideas. This slide toward reactive, as against active, thinking only accelerated.

At the same time, there was a technology boom, such as the Internet, making communication easier in fragments of copy (later, hyperlinks) about topics, garnering fast but fleeting consideration. My movie articles were generally, comparatively and necessarily concise. Movies back then were generally an investment of a few hours of time between parking and what comes after seeing a motion picture in a theater. Reading less than 1,000 words about a movie was, in today’s parlance, no big deal.

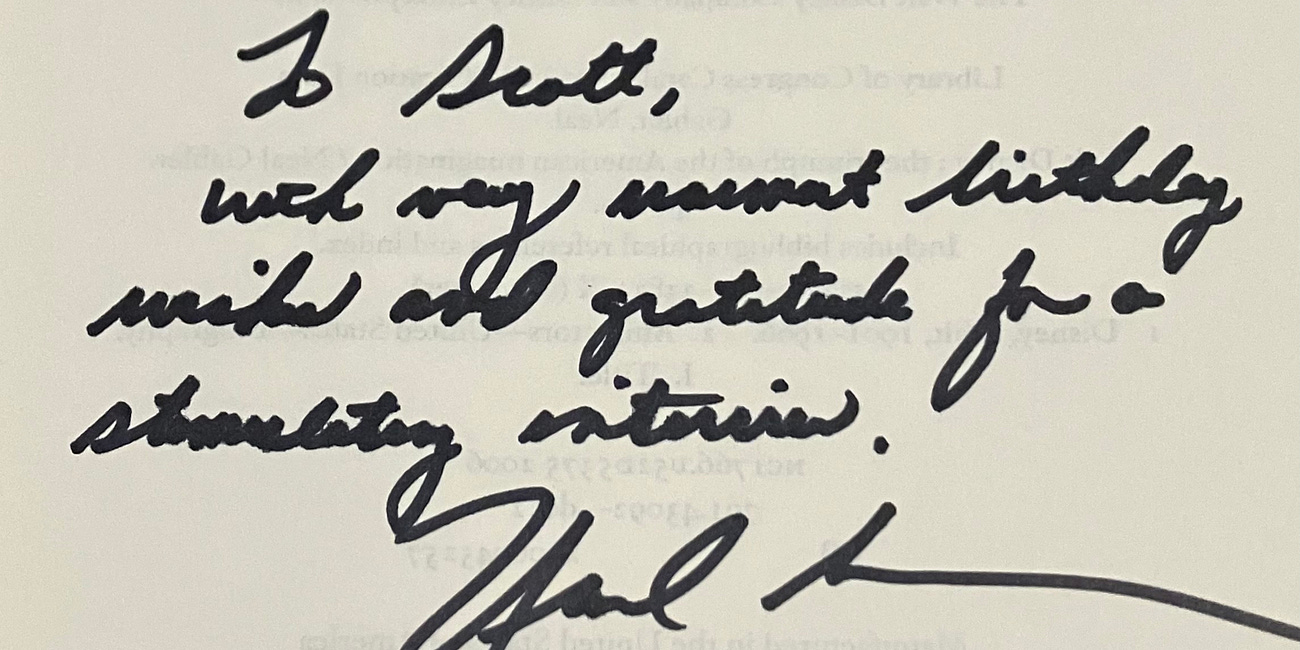

This, in daily practice for me as a writer, means taking any praise with caution or doubt. I can accept a compliment; I’m self-confident. Being dubious doesn’t mean I don’t like, appreciate, and, in a narrow sense, need praise and attention. I do. As I get older, as my birthday post shows, I choose to make an effort to seek and solicit sincere feedback from those who express interest in supporting my writing. I know it’s a small audience. But the smallest band of readers is powerful as far as I’m concerned. When someone delivers a compliment about a film review, why, how, when, where and what gets written, said or conveyed are relevant in assessing sincerity and depth. As the saying goes, and I hate this phrase, it’s just a movie.

Of course there’s truth in this. It’s difficult to gauge how seriously someone intends a compliment about something you’ve written. Kind words can be a casual convention. Someone might pay a compliment to pass time. A compliment may be fake or insincere. People can lie. To me, saying it’s just a movie is like saying: it’s just a life.

Years ago, I received cutting criticism in the shadows of Colorado’s mountains. This was during a 50th anniversary celebration of my favorite novel. The put-down came from a peer—a non-academic intellectual—who was present in a gathering of people, most of whom were complimenting my movie reviews. This person, a conference lecturer, said to me: “They’re just movie reviews. It’s not like writing about something serious, like philosophy.” The point was repeated for emphasis. The intellectual who said this is also a writer—a good writer. I took what was said seriously.

The writer isn’t wrong. The writer has a point. I think about the criticism from time to time. That I overheard the same writer, years later—at another conference in another city—raving about a motion picture which I know was probably discovered by this person after someone who read my review recommended the film doesn’t change the truth of the criticism. The critic contextualized the movie review. To the extent it’s just a movie, it is also just a movie review. Arguably, it’s no big deal.

Nevertheless, when I was asked by two young entrepreneurs to write film reviews, I took the simple act of writing a movie review seriously. At that time, I was writing commentary, features and news for U.S. media including newspapers. I had launched a paid subscription e-newsletter after the worst attack on America in history. I was reluctant to write movie reviews, which initially struck me, too, as frivolous. Because these were friends who pleaded partly based on admiration for my writing and partly based on an argument that my writing and editing would help them grow and make money—and because I wanted a break from writing about issues of war, controversy and politics—I agreed to accept their partnership stake offer as a side project.

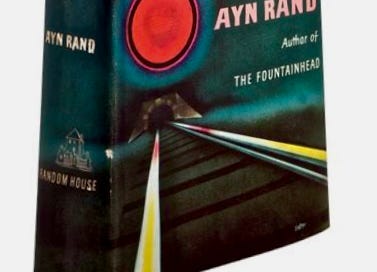

I started on the enterprise by investigating and formulating an editorial process. I went to a source I knew I trusted—Ayn Rand, which you probably anticipated—and browsed various indexes in books of Rand’s writing or lecturing such as The Art of Non-Fiction, a condensed, written version of Rand’s lectures on non-fiction writing, which I’d listened to on audio cassette. I came across her thoughts on writing a book review, which I had previously read while writing reviews of books. It’s short, but Rand is the world’s greatest philosopher, which means hers is a serious, deep approach with potential to change one’s life. I modified what Rand said about writing a book review and adopted it as my method for writing a movie review. It’s my approach based on Ayn Rand’s ideas.

Soon, I was being denounced in online forums—by “fanboys,” as the company’s founder, who backed me up without hesitation and on principle, called them—and attacked by movie studio suits. A Sony Pictures executive attacked me based on a mixed review of one of the scads of Spider-Man movies. This is how I knew the movie reviews were having an impact. My reviews were quoted, indexed and sampled for scholarship, press and promotional purposes across a wide spectrum—some still get quoted or reprinted—often in college textbooks.

I was offered bribes in varying attempts at influence peddling—I was repeatedly offered and rejected inclusion in Rotten Tomatoes, an aggregation site based on an idea which, fundamentally, is anathema to objective reporting—and I soon received death threats and notes in profanity waves from ranting pseudo-readers.

My negative review of a Chronicles of Narnia movie as religious propaganda elicited death threats. So did my column about Mel Gibson’s bloody film about Jesus Christ. Leftists were outraged by my thoughts on a movie by Michael Moore, which I also reviewed as religious propaganda. Ad hominem attacks with profanity generally came from professed leftists. Ad hominem attacks with insinuations or direct threats of death generally came from conservatives. When Objectivists disagree with my movies writing, they express why on blogs, forums and in backchat. The best Objectivists, such as podcaster Martin Lindeskog, blogger Gus Van Horn and many reading this article, publicly disseminate what they judge as my thought-provoking writing.

This brings me to my favorite novel, Atlas Shrugged, the epic 1957 novel by Ayn Rand, which was adapted for film. When a movie studio executive who read my Box Office Mojo writings, including the reviews, interviews and my column, gave me an exclusive on adapting Rand’s railroad-themed story—casting an actress of prominence as Dagny Taggart—I reported the news, which caused a stir. I conducted an exclusive interview with the version’s writer and director, published on the movie website.

The interview includes this exchange:

[Scott Holleran]: Is money—as Ayn Rand wrote in Atlas Shrugged—the root of all good?

Vadim Perelman: I have a great quote from Ayn Rand that I actually believe: “If there's a more tragic fool than the businessman that does not realize he’s an extension of man’s highest creative spirit—it's the artist who thinks that the businessman is his enemy.’ That should be on the masthead of your Web site. So, that answers your question—and that's from Atlas Shrugged.”

Later, when a libertarian businessman adapted the novel as a trilogy, I attended the press and advance screenings and reviewed all three films. This was not a meaningless or trivial task. I consider my coverage of the novel’s cinematic adaptation to be among the more influential episodes of my movie journalism. In retrospect, I was even-handed, objective and rational, which I think made reactions to the films, and undeveloped works in progress—including the Hollywood establishment’s reaction to the prospect of adapting Rand’s fiction for film—easier, simpler and less stigmatized.

The executive who’d granted me the Atlas Shrugged scoop also provided a crucial and formative impetus. After I’d rejected an offer to expand my role at Box Office Mojo when it was sold to a subsidiary of Amazon, we met at his office. I’d been conflicted and dubious about Amazon as a company, a conclusion I later came to appreciate, upon meeting with Amazon bosses at the Seattle headquarters. As we discussed my future prospects, the executive told me to create a blog. Whatever you do, he told me, keep writing about movies. I did. The first blog post was a movie review.

In the meantime, I’d met and interviewed Walt Disney Company Chairman Dick Cook at his office at the Disney studio, Oppenheimer writer and director Christopher Nolan at his office on the Warner Bros. lot and I met and interviewed artists at 20th Century Fox, Sony Pictures, Paramount and other studios. I saw La La Land, which I regard as 2016’s best picture, at Lionsgate. I met and interviewed Jon Turteltaub about the National Treasure films—also about his intelligent Travolta movie, Phenomenon—and other highlights include seeing and writing about the exquisite Green Book.

I strive to be objective. During the run-up to the heavily hyped release of 2005’s Focus Features movie, Brokeback Mountain, I became increasingly concerned that being gay could become a drawback to my ability to be objective in evaluating, judging and reviewing the film. Brokeback Mountain was a major Hollywood release. My coverage of the movie, which co-starred Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal, was extensive. I interviewed a studio executive about its marketing, which elicited a narrowly focused story about granting the benefit of the doubt, while also challenging prejudice and protecting the persecuted, to America’s middle class.

Knowing I’m gay, however, I wanted to get the journalism right, especially my review. After attending the advance press screening, which was more emotionally loaded and problematic—some audience members snickered and audibly expressed repulsion, which took me out of the movie—than I’d anticipated, I asked a studio executive for an invitation to attend a second press screening. I’m glad I did. Seeing the picture a second time clarified certain aspects. I wrote what I consider one of my best movie reviews. I think it mirrors Ang Lee’s haunting and cautionary film.

Other movie writing highlights include finding, discovering and interviewing the writer and director of Hidden Figures, whom I met and interviewed twice, as well as Hollywood titan Frank Marshall at his Santa Monica office, comedian and writer-director Mike Binder, who subscribes to Autonomia, and Martha Coolidge at her home in the foothills of Los Angeles, Jon Voight at his Benedict Canyon home, James Marsden in Burbank and Alexandre Desplat, Rachel Portman, Thomas Carter and Sam Elliott, whose remarks about Brokeback Mountain during my 2006 interview became controversial when they recently resurfaced.

In spite of this series—and this is the final installment about my 30 Years in the Press—looking back at past work is an induced, not a natural, effort or endeavor. That said, what springs to mind about movie writing that adds value or breaks new ground includes a series on Disneyland, deeper, analytical reviews of The Sound of Music, South Pacific, Oklahoma!, We the Living, Richard Jewell, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?, Schindler’s List, 12 Years a Slave and, this year here on Autonomia, Casablanca; also The Lives of Others, The Family Stone (a Christmas movie I love) and a Star Wars column in which I examine my growth from being an admirer as a boy to an adult judging the franchise as fundamentally bad.

Additionally, I’ve interviewed The Waltons creator Earl Hamner, Jr., who added a link to my interview on his website before he died, at his Studio City office as well as actors Bo Hopkins (American Graffiti), Earl Holliman and Shall We Dance director Peter Chelsom at my San Fernando Valley home. I was not starstruck—never have been—even when I met my one of my heroes, Olivia Newton-John, at her Malibu home during one of several interviews. When I met Channing Tatum at an event, he made a point to thank me for an early career review in which I’d noticed and praised his performance. During a showcase of young actors in Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Mellon University drama program, I did the same for a young actress named Patina Miller, who went on to success on Broadway.

Writing movie reviews, like all forms of writing, is a solitary enterprise. Besides seeing a film by myself, then writing the review (read my essays on somber, remoteness-themed films Inside Moves, Five Easy Pieces and Save the Tiger) reviewing a movie can be extremely isolating. This is because seeing a movie with an audience—the best way to watch a movie—often in the company of a guest, who is sometimes a loved one, necessitates an abrupt departure into an interior world in which the writer must create something abstract out of an experience which, at best, can elevate, even exalt, the writer to have an intense or euphoric sense of intimacy or belonging; detachment follows feeling attached. I experienced this while reviewing 2008’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, which I compare to the Serenity Prayer. While writing this year’s review of Equalizer 3, I felt strong emotions. Seeing a movie with someone you love can unlock deep and powerful emotion. Writing about the same film afterwards can be jarring and bittersweet. I’m figuring out why.

Meanwhile, in the realm of writing about movies, I’ll be remiss if I don’t include writing about those who, like me every day, choose to dance. Articles about Fosse, Nureyev and Fred Astaire stand on their merits. Years ago, after I opted out of Box Office Mojo and the start of its Amazon-owned deflation, irrelevance and oblivion, which I foresaw, I attracted the interest of a film director who’d read and admired my movie writing. He offered to film me as a dancer, which he later did. Incidentally, I’m probably going before the movie camera again to dance. Concurrent with my movies, fiction and other writing, I choreograph and dance.

Milestones in movie writing include meeting Sydney Pollack at his office on Sunset Boulevard—our wide-ranging interview is one of his last—my favorite living director, Lasse Hallström, in separate and distinct interviews about each, though not all, of his films, including An Unfinished Life, an inspiring and thought-provoking motion picture about the individualism nested in America’s Western mountains.

Similarly, writer and director Robert Benton, with whom I’ve discussed Feast of Love, The Human Stain, Kramer Vs. Kramer and Places in the Heart, movies I reviewed and regard as worth watching, stands out. Mr. Benton read and became an admirer of my short stories, which I’m happy to know he recommends. His wife, Sallie, an artist and painter, once wrote to me that she values my Kramer Vs. Kramer interview because she learned things about her husband and his artistry that she had not previously known.

This is what good movie writing can do; report, examine, judge, contextualize and elucidate a movie and the one who makes it—enticing the reader to judge for himself. I had interviewed Sallie Benton’s husband, the artist who wrote and directed 1979’s Oscar-winning Kramer Vs. Kramer, in the same Hollywood hotel where Oscar’s first ceremony took place nearly 100 years ago. I was attending a Turner Classic Movies (TCM) classic film festival where Robert Benton was a featured and honored guest.

This is the future of the movies. Occasionally, new movies with promise may come, go and gain attention, scorn—even death threats—and affection. Belfast, Elvis, Rocket Man, The White Crow, Green Book and rare new movies of quality may get ink. But if it’s movies you love, look to the classics for the best in writing that’s yet to come.

Related Links and Articles

Movies: Casablanca

Do you know Casablanca? If so, have you seen the movie in a theater? What do you think it means? I first saw this 1942 Warner Bros. movie on television. Later, I watched Casablanca on VHS, then on DVD and again via streaming. Years later, I watched Casablanca

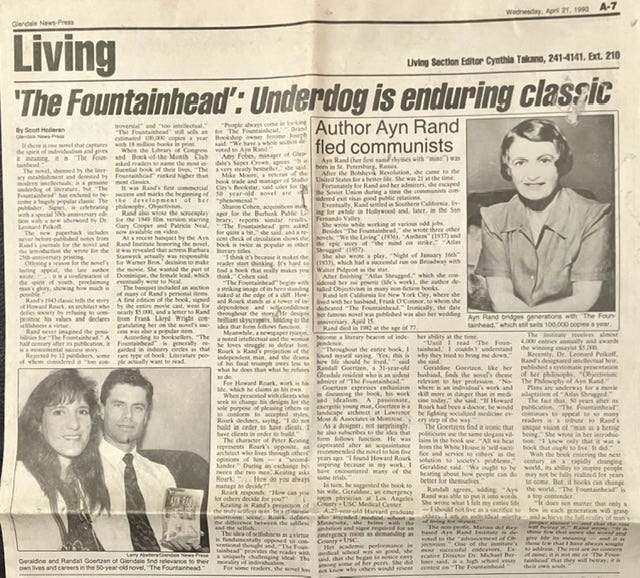

Thirty Years in the Press

Today begins my 30th year in journalism. The article (not headline) pictured above, the first writing for which I was paid with money, was my idea. It was published 30 years ago today, beginning a career in journalism which continues with Autonomia.

Thirty Years in the Press

Interviews have always been a major part of my journalism. From my articles for a school newspaper and an alternative press in Chicago to Autonomia, the interview is one of my most practiced, skilled and methodical formats. I possess a natural (and arguably inappropriate) curiosity in the company of stars, strangers and ordinary people. Even as a boy, i…

Thirty Years in the Press

Strictly speaking, I am not a news reporter, though I do report the news. But, when I have and do—throughout my three decades of journalism—I tend to write in extremely focused detail about certain issues, history and themes. This approach has led to some of my most commercially success…

Thirty Years in the Press

This is the fourth in my five-part series on 2023 as my 30th year in the press—part one covers my first paid article in journalism, part two focuses on the interviews and part three reviews my news reporting—since the late 20th century. An early part of my 30 years in journalism involves books. This was a consciously chosen part of my strategy. I was young. I knew I wanted to learn. I knew that reading books, especially books written by authors with whom I disagreed, could help. I also knew that writing about books could put me in the league of literary writing I wanted to master. I sought to meet and interview the world’s greatest authors, which could be afforded by book journalism. I could get to know an author, I figured, during an interview—at my initiation, request or insistence, most of my interviews were conducted in person as was (and is) my general reporting practice—and, as an author myself, I would have an opportunity to learn what writing, promoting and, above all, thinking about a book and its mass market publication means both in theory and in practice—within months of going to press.

It was fun, entertaining, and enlightening to read about your journalistic journey! Hey, I like that, lol.

I remember when I was trying to find a movie reviewer that I could trust because most of them out there were truly dreadful along with so many of the movies made these days. I was delighted to find you were doing it as a regular gig, because I'd read many of your articles before and I knew you were an Objectivist. I knew what you wrote would be an honest assessment of the movie coming from a philosophical base I agreed with. I wasn't ever disappointed except when I found out you had left Box Office Mojo, and would no longer be writing reviews as a regular thing.

As to 'just a movie' - movies, like all art, are incredibly important. As with so many things in life, I thank Ayn Rand for this perspective. She is the first one to make it clear to me just what art is philosophically, how important it is to our lives, and why so much of what was currently being put out in all forms was absolute dreck. And I finally understood why some stories moved me so, and made me feel good about myself and hopeful about our culture no matter how degraded it was becoming.

So, writing about movies is damned important because it can assist all of us in truly understanding these tiny windows into our philosophical premises, which, if done well, can help improve all our lives.