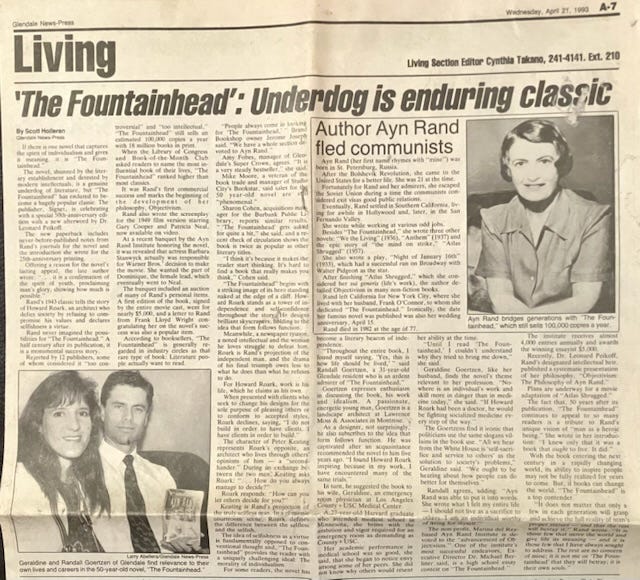

Today begins my 30th year in journalism. The article (not headline) pictured above, the first writing for which I was paid with money, was my idea. It was published 30 years ago today, beginning a career in journalism which continues with Autonomia.

Three reasons why I’m writing about myself

Most of my articles tend to be in-depth stories about culture and the arts, which started with this first article. Throughout 2023, I’ll re-examine my years in the press. Retrospection generally gets what I regard as an undeservedly bad reputation. I don’t write in reflection about my past with frequency, though I know that self-reflection about one’s prior actions, achievements and ideas can improve one’s introspection. I’m initiating this series (and started Heartstrings for the paid subscriber) for three reasons. First, I’m at the beginning of a later part of my writing career. Second, I’ve created Autonomia expressly as an experiment in the free press for readers who choose to subscribe to and…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Autonomia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.