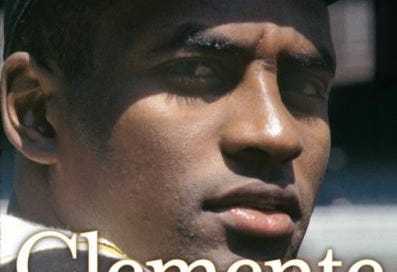

Book Review: Clemente

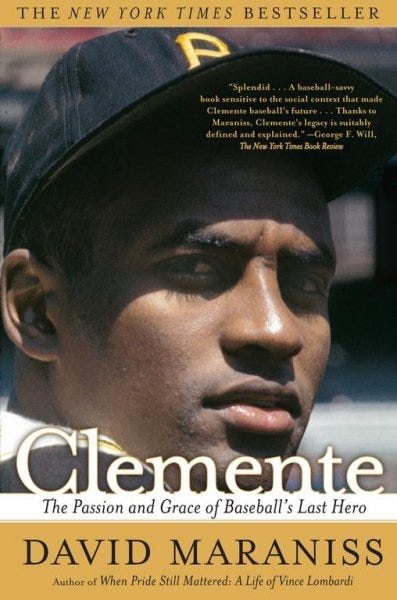

Thoughts on Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero by David Maraniss

Roberto Clemente’s life and career is an epic tale. Puerto Rican Clemente played Major League baseball for the National League’s Pittsburgh Pirates in record-breaking home runs, hits, games, championships and World Series. Clemente’s life, which ended on New Year’s Eve in a 1972 plane crash that shocked the nation, is simply larger than life. David Maraniss, a journalist for the Washington Post who covered Bill Clinton and the Virginia Tech mass murder, as well as Vince Lombardi in a biography, indulged his obsession with Roberto Clemente. This highly detailed 2007 biography, Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero, is the result.

Maraniss admires Clemente for what he explicitly regards as Clemente’s self-sacrifice. In this sense, the author is certainly part of sports journalism’s and Washington, DC’s status quo; he never wavers or questions altruism as the highest morality—accordingly, Maraniss makes bad judgments and wrong conclusions—and he’s candid about his moral …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Autonomia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.