Series Review: Taken Hostage (PBS)

Iran’s November 1979 attack on America is the topic of this four-hour film

Last year’s two-part PBS American Experience series, Taken Hostage, written, produced and directed by Robert Stone, merits renewed attention. This isn’t merely because Iran sponsors terrorism—Iran hasn’t stopped sponsoring terrorism since the former Persia became an Islamic dictatorship—or because its spawn attacked Israel on October Seventh in an act of war, mass murder and savagery, taking new prisoners.

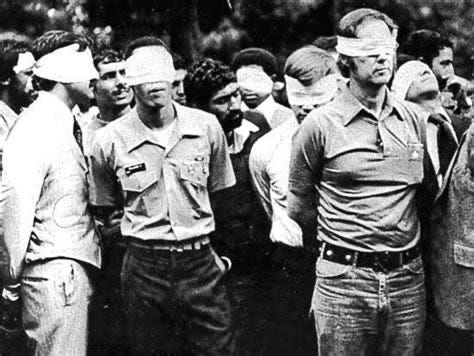

An Islamic-Arab terrorist axis of religionism, nationalism and barbarism did not begin on November 4, 1979, when at least 66 U.S. civilians, Marines and diplomats were seized, tortured and held by Islamic terrorists at the American Embassy in Teheran—52 Americans were held prisoner for 444 days—with Iran’s sponsorship. From Black Tuesday to whatever mass death is planned by Iran and other states that sponsor terrorism, the rise of terrorism comes from America’s and the West’s appeasement of that single act of war on that November Fourth.

Indeed, the PBS program title, Taken Hostage, like the term for recently captured Israelis, propagates falsehood. The Americans—like today’s captive Jews and Israelis—are not really hostages, not if this term implies an act of force initiated to induce a quid pro quo exchange.

There’s no explicit, discernible or actionable exchange possible in the 1979 (or any terrorist) attack. To the extent meeting demand for releasing prisoners is possible, it’s a sham (as evidenced by the Munich Olympics massacre and West Germany’s post-slaughter facade). Innocents taken—then and now—are prisoners of war.

Taken Hostage, framed within the romance of former prisoner Barry Rosen and wife Barbara, pretends otherwise—an error, oversight and serious flaw. The four-hour film, featuring interviews with foreign correspondents Hilary Brown and Carole Jerome, Carter administration senior national security adviser Gary Sick and, most notably, Colonel James Roberts, member of a top-secret U.S. commando unit, also makes no attempt to enumerate, let alone contextualize, captured and tortured Americans. The “hostages,” except for the Rosens and a few others, are shifted into the background. There’s no attempt to chronicle or profile those held prisoner; there’s not even a mention in the PBS series of the original number of seized Americans.

This means there’s no reporting that religious activist Jesse Jackson, whose career hinged on pre-judging, baiting and blackmailing businesses based on blood, skin and race, worked with Iran for the release of only black prisoners (and selected females). There’s no reference to businessman Ross Perot, who defied the U.S. government to wage a daring paramilitary operation rescuing his own employees. Canada’s rescue, the subject of the movie Argo, also gets no mention.

Taken Hostage lacks a timeline. It’s absent discourse about which country (or countries or who) initiated, sponsored and abetted the attack. The viewer’s left to judge Iran while being denied access to relevant facts. Instead, Iran’s history, i.e., the rise and fall of Mossedegh and Iran’s nationalization of the oil that Britain discovered and refined, is tilted in Iran’s favor—down to the oil well included in the series’ logo. Journalist Jerome, admitting only in retrospect, though concealing this from her audience and the public, that she was romantically involved with one of Iran’s officials, Sadegh Ghotzbzadeh—who was later executed by Iran—comes off as an Iran apologist.

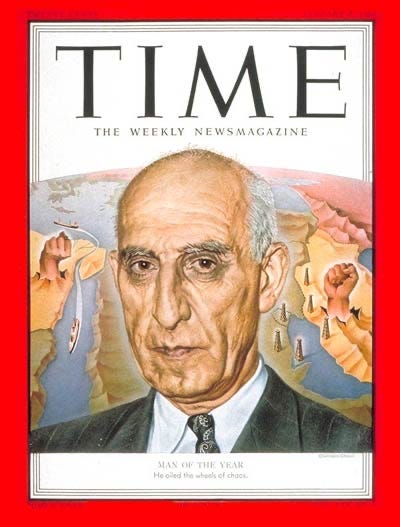

So does Taken Hostage, which overestimates Iran’s power (the embassy siege occurred long before Barack Obama’s deal strengthened the terrorist-sponsoring state). For example, in a reference to Time’s 1952 cover of Iran’s pro-Soviet leader as its Man of the Year, narrator Stephen Kinzer neglects to include the publication’s subhead concluding that: “He oiled the wheels of chaos.” This omission falsely gives the impression that the U.S. press was agnostic toward the Soviet puppet.

Gary Sick makes the claim that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini single-handedly brought down Iran’s 2,500-year monarchy, which is not true. The Shah was brought down by the Shah—by his fundamental acceptance of mixing state and religion and his complicity with Islamic jihad—exacerbated by Iran’s nationalism. Iran’s deeply rooted in nationalism, which was propelled by Nazi Germany. The program, which lacks titles, so you rarely know who’s speaking, skirts the monarchy‘s end, obscuring the Iranian people’s role in the rise of Islamic totalitarianism.

Taken Hostage is Robert Stone’s ninth movie for PBS’s American Experience. The film does contain original reporting worth knowing—as long as the viewer notes the forementioned gaps, discrepancies and flaws.

For example, the series begins with ex-prisoner Barry Rosen’s narration: “Some young woman cut the [embassy gate’s] chain…” Then, a female radical Moslem appears, addressing the press in Teheran.

“Who are you?” Someone asks.

“I’m part of the students following the … [Islamic mystic],” the jihadist replies. So filmmaker Stone doesn’t totally drop the context of religion as the primary motivation for the woman’s acts of evil. Showing the Shah in archival footage, such as interviews, which both demonstrates his faith and his tyranny and explains Khomeini‘s subsequent rise—sanctioned by President Carter’s evasive foreign policy—Taken Hostage exposes the roots of this weaponized religious state.

For example, overrated TV personality Barbara Walters can be seen and scrutinized with her simpering, second hander reporting from Persepolis. Overrated filmmaker Orson Welles narrates nationalist propaganda dubbed “Flames of Persia”; both Welles and Walters appear as eager shills for the Shah. Familiar U.S. political figures—Nixon, Kissinger, Haig—appear with regard to Iran’s role in U.S. foreign affairs.

Taken Hostage, in spite of itself, shows that Iran’s moderates—Abolhossan Bani-Sadr, Sadegh Ghotzbzadeh—brought Khomeini to power. With footage of Khomeini returning from exile to Iran on an Air France 747, a reporter can be heard saying: “we have never seen him smile or show any sign of emotion” as the mystic glares into the camera with contempt. When the jet touches down in Teheran, someone asks Iran’s new dictator the fawning question: “How do you feel?” The Islamic tyrant answers: “Nothing. I feel nothing.”

A British reporter refers to the future mass murderer—who would sentence an artist, Salman Rushdie, to death and bear responsibility for the mass death of Americans including 283 U.S. Marines—as a “frail old priest.”

The climax of Iran’s Islamic revolution unfolds as pretext to storming the U.S. embassy. “Gunmen were everywhere,” “it was anarchy,” “it was like being a reporter with a camera crew at the French Revolution,” and, in one of the more telling lines in terms of gauging the coming confluence of media, barbarism and a world at nonstop war: “Most of the executions were televised.”

Recalling his time in Teheran, which was once a modern metropolis, partly thanks to the Shah‘s industrialization, retired U.S. Army Colonel James Roberts says:

I came back to the States and was debriefed by a number of [government] agencies. My advice was: we should break our diplomatic relations [with Islamic Iran], close the [embassy] compound—[it was] too big, too visible, [there was] too much bad blood—I was convinced our relationship was going to continue to deteriorate.”

Taken Hostage reports that, before the November Fourth attack, the U.S. embassy was stormed on Valentine’s Day in 1979—few of today’s journalists and historians bother to mention this crucial fact—as ABC News anchorman Frank Reynolds (Nightline personality Ted Koppel’s superior predecessor) simply notes that: “the U.S. embassy [was] seized by an angry mob.” The program shows that, later, while fleeing Iran, the dying Shah almost went to Palm Springs—Carter cruelly withdrew the offer—and, omitting his trip to Panama, traces the terminally ill U.S. ally’s itinerary to Egypt, Morocco, the Bahamas, Mexico and the New York Hospital Cornell Medical Center.

Also on display: Carter meeting at the White House about inviting the Shah to America upon learning that the old ally was dying—with everyone claiming that Jimmy Carter couldn’t say No to the Shah and President Carter, according to Gary Sick, responding: “You’re all unanimous that we should take the Shah in but I wonder what you’re going to say when they take Americans hostage in Iran.” The Shah was subsequently admitted to New York City yet this is an admission that the United States government knew in advance at the highest level that the risk of Iran attacking America for admitting the Shah was a specific, clear and imminent danger.

As Barbara Rosen, captive Barry’s wife, puts it: “There was no reason to keep the embassy open knowing the threats that [were] made against [the American] people.” Mrs. Rosen’s commentary is followed by footage of Iranians in ski masks with guns.

The second and concluding episode of Taken Hostage shows an act of vandalism on the Statue of Liberty in New York City, followed by reports of Jimmy Carter’s “crisis of confidence,” the taken prisoners’ suicidal tendencies and depression, jihadist Mary, who became Vice President of the Moslem dictatorship, and others in Iran’s Islamic regime being educated in U.S. schools and Carter using the phrase “Iranian terrorist.”

Has any American president publicly used the phrase since?

Besides scholarship and archival assets, the best of this American Experience is excellent animation of President Carter’s failed military rescue, a compelling point-by-point re-enactment, including what went wrong, by Col. Roberts, who participated in the mission. To this day, questions about what went wrong remain unanswered.

Robert Stone’s Taken Hostage, partly narrated by author and journalist Stephen Kinzer, whom the Washington Post touts as being “among the best in popular foreign policy storytelling,” apparently draws from Kinzer’s work. Barry and Barbara Rosen, who’ve been married for 50 years, emerge as resilient Americans with something meaningful to say about this unavenged act of war. The program has value, though its flaws stand out, particularly in the aftermath of Iran’s October siege on Israel.

Minimization is a tactic to deny Iran’s crusade to annihilate the West. This starts with acceptance of the lie that seizing and terrorizing innocents can honestly be judged as hostage-taking. On November 4, 1979, Iran’s jihadists captured U.S. prisoners in a religious war. America responded with appeasement, which empowered fundamentalist Islam and let terrorism spread. Taken Hostage ignores, downplays and trivializes this essential fact and context. The series makes evident that those creating, making and participating in Taken Hostage—also PBS and American Experience and, frankly, most Americans—probably know it, too, and choose to evade reality.

The subtitle of this series is The Making of an American Enemy. Did Americans have terrorism coming—does America deserve mass death by jihad? This series and the prevailing viewpoint propose that the unequivocal answer is at least partly Yes. On Taken Hostage’s own terms, though, the opposite is true. America, if not exactly Americans and her dominant leaders and intellectuals, is innocent. As the Rosens argue and demonstrate, those taken as prisoners of this unprovoked, undeclared and, apparently, unmentionable, total war on the West were—and are—innocent. America’s enemy and enemies are made among Moslems in mosques and madrassas and everywhere people are born and bred to believe in irrationalism.

Related Articles

Report: Salman Rushdie

This is the first article in Autonomia’s debut series of reports about Salman Rushdie, the writer targeted for death by Iran on February 14, 1989. Rushdie was stabbed in the United States of America in an assassination attempt on August 12, 2022. Who is Salman Rushdie?

Report: Salman Rushdie

This is the second in Autonomia’s debut reporting series about Salman Rushdie, a writer condemned to death by Iran on February 14, 1989. On August 12, 2022, Rushdie was repeatedly stabbed in the United States of America. Read the first report here. Why does Iran condemn Salman Rushdie?

Report: Salman Rushdie

This is the third in Autonomia’s series about Salman Rushdie, the writer condemned to death by Iran on February 14, 1989. Rushdie was savagely stabbed in the United States of America in August. Read the first report, about Rushdie, Iran and its mystic-dictator who ordered Rushdie’s assassination,

Series Review: Hemingway (PBS)

Billed on America’s state-sponsored television programming, Public Broadcasting System (PBS), as “a film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick”, the three-part Hemingway stuns, informs and stimulates. This is Burns’s best documentary. I learned more about the 20th century’s influential, suicidal and bestselling writer than I’d ever known.

Series Review: ‘I, Claudius’ (PBS)

In 1998, the Modern Library ranked I, Claudius—the first of two fiction books by Robert Graves about the Roman emperor—on a list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. The novel ranked 14th. BBC adapted both Graves novels as a 1976 television series, which aired on state-sponsored PBS in America. It, too, was titled

We have been at war with Iran since the moment those people were taken 44 years ago, only we are too damn stupid and cowardly to acknowledge that fact. If we had taken the actions necessary then, that the previous generation took with the Japanese in 1941 we would have avoided the tens of thousands of deaths the world has incurred since then including the current atrocities in Israel. And taking down the theocratic monsters in Iran would have been far simpler and quicker than wising up the Japanese, with far less bloodshed. We truly live in moronic times.

Thanks for this review. For a long time, I have scornfully labeled NPR as "National Palestinian Radio." I guess now I can also refer to PBS as the "Palestinian Broadcasting Service." Also, thanks for distinguishing between a "hostage" and a "prisoner of war."