Report: Salman Rushdie

Part 2: What’s Iran’s conflict? 1989’s death decree and August’s assassination attempt

This is the second in Autonomia’s debut reporting series about Salman Rushdie, a writer condemned to death by Iran on February 14, 1989. On August 12, 2022, Rushdie was repeatedly stabbed in the United States of America. Read the first report here.

Why does Iran condemn Salman Rushdie?

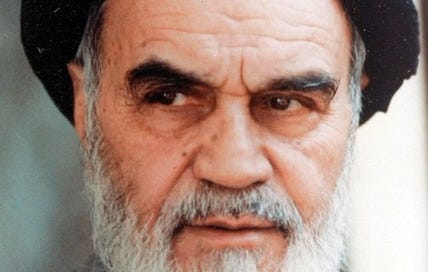

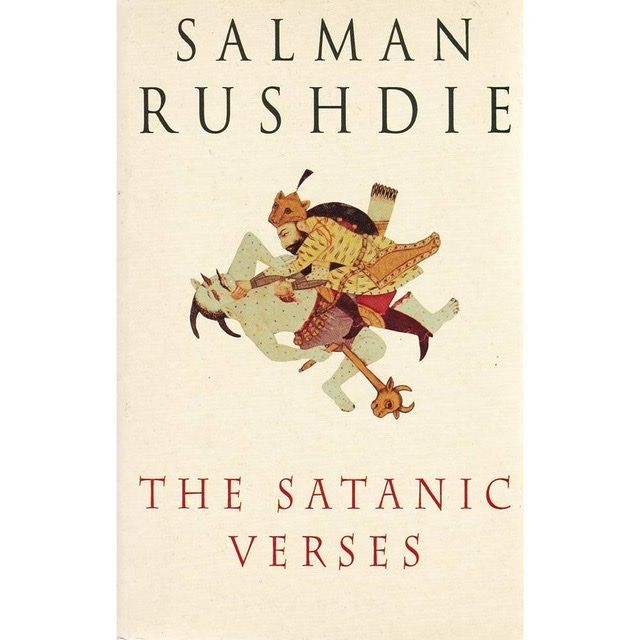

When author Rushdie wrote The Satanic Verses, according to the theocracy’s ayatollah—its dictator—the writer committed blasphemy against Islam, Iran’s state religion. Rushdie was condemned to death. Today, Iran vows to kill the infidel (which, according to radical Islam, means anyone who’s not Moslem), destroy America and annihilate Western civilization. Iran also condemned Rushdie’s publishers and the book’s agents, including bookstores, to death.

What are the facts of Iran’s death decree?

“When Salman Rushdie wrote his novel The Satanic Verses in September 1988, he thought its many references to Islam might cause some ripples,” Julian Borger rec…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Autonomia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.