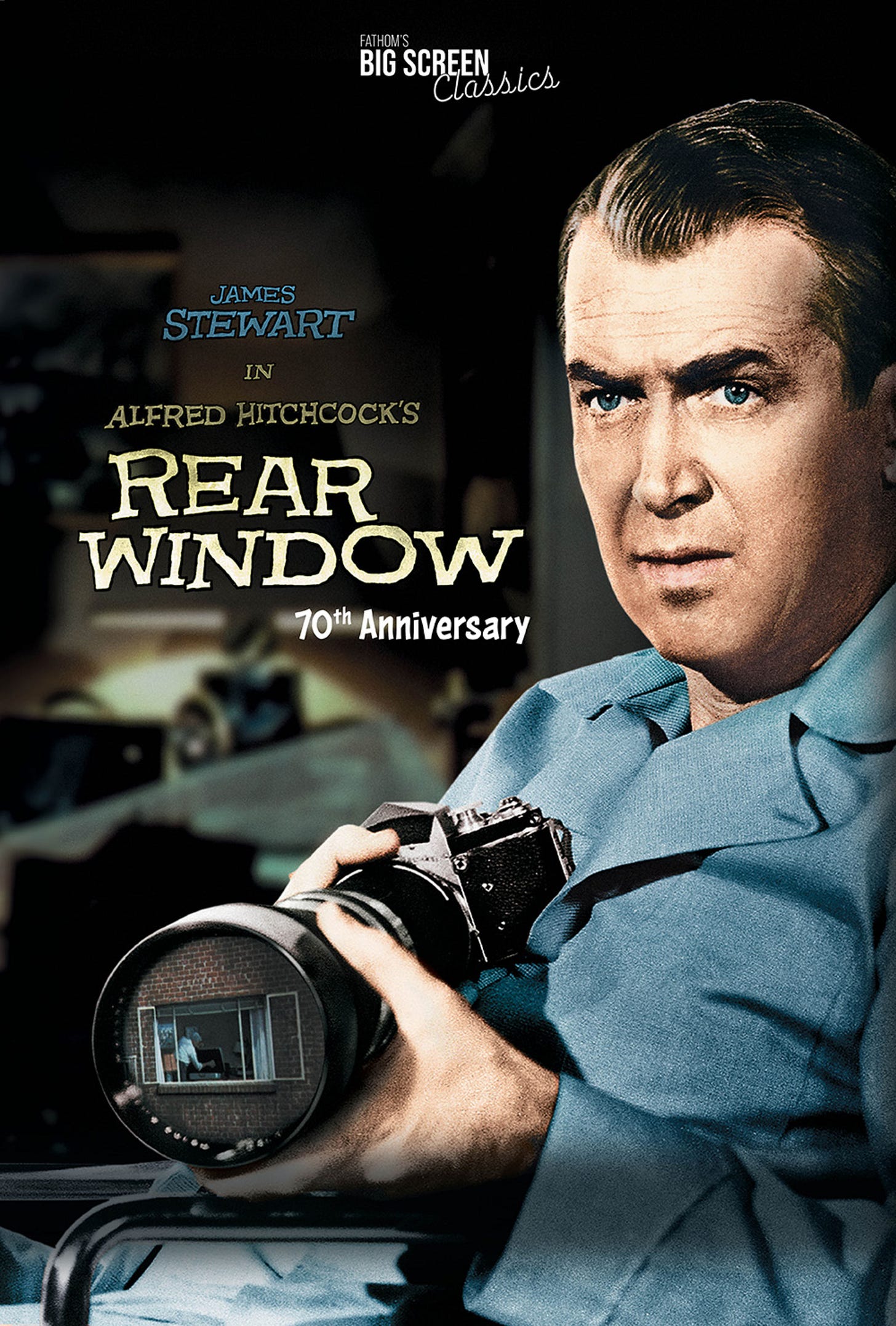

Movies: Rear Window

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 masterpiece of moral, psychological and existential conflict, tension and resolution culminates in an affirmation of art, unity and romantic love.

At its center, Paramount Pictures’ 1954 motion picture by Alfred Hitchcock, based upon a 1942 short story by Cornell Woolrich and adapted by John Michael Hayes, both dramatizes and stylizes man as a social being—man the producer, trading with others; man the citizen, abiding the law; man the neighbor—the one in the many—man the consumer; man the avenger and, finally, perhaps triumphantly, as if this is his proper reward, man the lover, the romantic ideal. The colorful picture story, neatly framed, angled and arranged, encompasses all of these in three main characters: handicapped photographer Jeff (James Stewart), his aristocratic girlfriend Lisa (Grace Kelly) and his insurance company nurse Stella (Thelma Ritter). Raymond Burr excels as neighbor and traveling salesman Lars Thorwald, as does Wendell Corey as ineffectual policeman Tom Doyle—cops are rarely depicted as efficacious in Mr. Hitchcock’s movies—yet the couple and their surrogate mother are the trio that forms the moral core of Rear Window.

That the Stewart character, Jeff, struggles to heal from pain and suffering—conceivably psychological as well as physical—adds an intriguing layer to Rear Window. An opening sequence begins with the sight of birds, followed by a cat, followed by the invasive whir of a hovering, surveilling helicopter above the Greenwich Village courtyard of backend apartments, embedding a predicate for the ominous potential for conflict at the outset, blending both a natural and manmade sense of tension, trouble and doom. Before the camera pans to peek at an older artist being taunted by a radio advertisement pegged to age, the shot holds on a cast that’s coming off in a week—and it’s constricting Jeff, the field photographer, who’s desperately trying to scratch an itch. This—helplessness—silently mirrors and bonds both an artist trying to create against the clock and a man of action imprisoned within his own home.

Jeff’s an enigma, even by name. He goes by the pompous or pretentious L.B. Jeffries—he’s simply Jeff to his romantic mate, whom he partly (and wrongly) regards as too good to be true—and, throughout the story, he holds back, pushes away and withdraws like a retractable lens. To his credit, he sees what he sees, judges and acts upon what he thinks he knows. It’s his caregiver-nurse-surrogate mother Stella who provides the most consistent lesson in being objective. During her physical therapy session, Stella tells Jeff of having forecast the October stock market crash of 1929. She had been nursing a businessman with a motor vehicle company, noting his emotional state, especially his anxiety. Having established pretext and credibility, Stella turns her judgment toward her patient. She baldly tells Jeff to get serious about making an emotional connection and commitment to the woman he’s dating. Marrying Lisa could be his best romantic choice, Stella all but counsels.

This is what Rear Window showcases with discretion and razor insight: the ability to think, reason and judge and, with tact and timing, to act upon one’s best judgment. This is why the movie’s a masterpiece of moral, psychological and existential conflict, tension and resolution. It gets better, however, which is probably why most audiences adore this movie with no clue as to why—amid its depth, burrowed into the whole picture, Rear Window is flush with flourish, color, strokes, shadows, signs and small, intimate scenes of humor, pathos, heartache, triumph, grief, sadness and desperation.

For example, after Stella’s stern forewarning to Jeff to get married to Lisa, Mr. Hitchcock sets upon two caged lovebirds, as if to cast doubt and deepen the movie’s mystery: whether man and woman can reconcile their relationship and whether they can achieve autonomy in the world at large. This is because, Rear Window dramatizes with wonder, it’s a hard, cruel world and we’re all being watched and observed—caged and surveilled—as well as being the observer. Add to this the entrance of mostly unseen newlyweds and their daring (for 1954) stamina for sex.

Having established the mysterious man/woman sexual-romantic premise—contrasted by a damaged or broken couple across the courtyard—in comes cool, confident, steely Lisa in her striking, elegant, simple Edith Head designs. Kelly as Lisa is in her element as an aristocrat like an Ayn Rand heroine with a rational mind, an athletic streak and a tendency to go rogue. This is Grace Kelly at her best. During an early appearance, she bundles her potential assets, cashing in on Stella’s affirmation, and essentially presents herself with a line of unmitigated arrogance and pride: “Dinner at 21.” Whatever Jeff knows of conquering and capturing nature, Lisa knows of conquering and capturing beauty, panache and simplicity.

On cue, a marital contrast appears. Raymond Burr’s Lars Thorwald expends some degree of effort to prepare a meal for his bedridden wife, adding and presenting a flower with the meal, which he serves on a tray to his apparently ailing wife, with whom he has previously been short in a quarrel of some type (in which the wife appears to mock and emasculate her husband while deriving sadistic pleasure). In this pivotal scene, the wife rejects the flower—not the meal—humiliating vulnerable Mr. Thorwald. This is a small gesture and scene, however, it later redeems itself in a climactic confrontation. Lars Thorwald’s a skillfully written role with layers like most of the story’s subsidiary characters. Raymond Burr’s performance is exquisite. He makes the most of his physically large body and his slow-burning facial expressions. Above all, the opposite of binding, abiding and understanding romantic love—being caustic, hateful and deliberately misunderstanding in ridicule of romantic love—sets the picture’s plot and thematic tone; the audience glimpses what becomes of love when one lets love turn to hate.

What comes next is one of the most marvelous montages in motion pictures. In a series of barely detectable movements adding up to a sequence of motion after the stillness of Jeff’s sudden realization that a murder may have been committed, Mr. Hitchcock unfurls a dog being slowly lowered in a basket, a spinster gently crafting fabric with a sewing machine and a sculptor sculpting. It’s an almost sensual fusion of three women being industrious, resourceful and artisanal. These three motions foreshadow handicapped Jeff’s immobility when faced with evil and what’s to become his reliance on the woman, the artist and industry to save and enrich his life.

This sensibility congeals in a short, subsequent scene in which, for the first time, Lisa and Jeff unite over a fleeting issue; turning on an electrical light. Lisa, drawn into Jeff’s emerging murder theory, chooses to follow Jeff’s instruction after trusting and acting on her judgment—hers is a crucial choice to act in partnership with her lover—again, the opposite of Mrs. Thorwald’s hatred of and opposition to her husband.

In the next scene, a spinster becomes a victim of sexual assault, underscoring that Rear Window—the definitive Fifties film in a decade otherwise known for conformity, sexism and allegiance to the status quo—is liberal, not conservative, and liberated, not dated, in contextualizing sex, woman and man. The other two women of the motion montage—the sculptor and the dog owner—are about to get rude reality checks, too.

The most searing moral and emotional turning point of Rear Window comes with the loss of a loved one. “Did you kill him because he liked ya—just because he liked ya?” —someone asks while in a blended expression of pure, raw wonder, innocence and outrage, like an unanswerable outcry or plea for justice. Whether and the way the courtyard residents, all of whom hear or can hear the grieving person’s lament, reply casts the story into a whirlwind of breathtaking plot twists.

For example, a party hosted by the artist—a musical composer and songwriter—marks a fascinating double-edged point. The cocktail party, which serves as both catalyst for artistic pursuit and contrast to Jeff’s lonely days and nights with a sense of belonging and being part of something, shows a jarring, jaded, cynical reaction to death, grief and expression of emotion. The party’s both a potential launchpad for art and springboard to despair. The party’s a party in which the guests are utterly devoid of empathy. Yes, Rear Window’s a microcosm, as most critics and classic moviegoers know. The party’s a microcosm of a microcosm—it’s tucked into a love story about how people can learn to love one another in a world gone (or going) hard, bad and wrong. No wonder this movie’s relevant. It forecast the coarsened, cruder future.

Alfred Hitchcock cuts from cold-blooded party guests to an overhead shot of the one in the many—Jeff, the crippled, lone man who sees with his eyes, snaps shots with his camera and judges with his mind—who refuses to submit to the herd mentality. It’s as if, in that moment, watching a stranger expressing total vulnerability, this guarded, cautious, wounded man decides to exercise his free will in favor of his highest values, knowingly going against what everyone else presumes. In the overhead shot, an abrupt departure from the film’s perspective, Jeff comes alive, physically, emotionally and intellectually, grabbing materials to write a note to the man he suspects of cold-blooded murder. That Rear Window hinges upon an exercise of free speech in writing strikes me as a powerful marker for the film’s 70th anniversary.

Jeff’s handwritten note raises the stakes and single-handedly challenges the police—i.e., the government’s most vital role—the collective (i.e., the party guests) and the status quo. As helpmates Stella and Lisa prove themselves and their shared values at great risk of danger, Jeff forgets himself and answers the telephone thinking it’s the policeman (Wendell Corey) he’s been desperately trying to persuade and enlist to investigate. Hearing the distinct click—possibly the slowest and most bone-chilling click in Hollywood history—(pardon me, but this is genuine click bait), Jeff’s expression turns from enthusiasm to terror.

The plot goes dark. Yet Mr. Hitchcock turns the dark twist into light with an unforgettable, slow, magical mastery in which the decision to choose death fans out to the affirmation of life and a triumph of the good made possible by the expression of art. Mr. Hitchcock does this with emphasis on the creator—not the destroyer—relegating evil to its proper scale of importance and bathing darkness in light.

By the end of the thrill, and too many critics note or stress only the movie’s thrills, dismissing its philosophy, depth and meaning, older Stella—who masks her youthfulness—starch Lisa—who reserves and taps her bravery—and Jeff—who tenses against his greatest strength; his vulnerability—rise and shine despite the terror of helplessness and powerlessness. Each exhibits real, heroic courage in exhausting and fabulous displays of athletic rationality. The unlikely, outwardly timid trio act in unity and harmony toward making the world better, stronger and more rational through realizing a romantic, realistic sense of life.

The proof lies in the neighborliness which pays off when Jeff is in peril at the end of the story—possibly the end of his life—as the world gloriously and with everyone suddenly in love with life becomes one in which he wants to belong. Rear Window in this sense tantalizes the senses. It makes you want to live here—with a perspective which urges you to accept color, light and love in the dingiest backends—and, awash in everything bad, good and mediocre, Rear Window makes you want to be alive.

Related Articles and Links

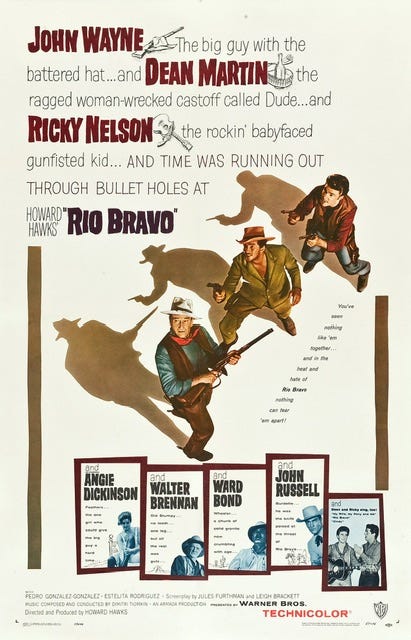

Movies: Rio Bravo

Watching Rio Bravo is time well spent. The classic 1959 Western by director Howard Hawks is deceptive in its goodness, so that it’s easy to underestimate the value. Many of today’s Americans take John Wayne’s sensibility for granted or they hold it in contempt, if they know of him. In

Sidney Poitier Shrugged

Today is Sidney Poitier’s birthday. From his early pictures, such as No Way Out, A Raisin in the Sun, Edge of the City, The Slender Thread and The Bedford Incident to the year he starred in the top three moneymaking movies, one of America’s best actors displays passion, verve and integrity. Mr. Poitier embodies individualism onscreen.

Obituary: Peter Bogdanovich

This is not comprehensive. The best movie-themed obituaries are published in The Hollywood Reporter. You can read Peter Bogdanovich’s in that trade publication here. Turner Classic Movies (TCM) and Leonard Maltin also posted remembrances.

Movies: Casablanca

Do you know Casablanca? If so, have you seen the movie in a theater? What do you think it means? I first saw this 1942 Warner Bros. movie on television. Later, I watched Casablanca on VHS, then on DVD and again via streaming. Years later, I watched Casablanca

I should be used to it by now, but your insights into "Rear Window" leave me awestruck. Not that I agree with you, but because I had no idea. It has been a long, long time since I saw "Rear Window", but my memory of it is one of several Hitchcock thrillers that are always good and interesting, but not terribly philosophical or having much more than surface entertainment value. It appears I am seriously wrong about that, and I am going to see if I can find it to watch it again tonight. Thank you, once again, for your deep analysis of something that can bring much more value to my life.