New, grief-themed articles reflect personal thoughts and writing about loss. In recent months, I’ve been reading and learning in the aftermath of several, simultaneous losses, including the death of my father. I’ll publish my thoughts. Thanks to the same source that recommended a romantic relationship book I reviewed earlier this year, Attached, I’ve read a book which affords a radical, new and better approach to grief.

In the meantime, I reviewed Taylor Swift’s newest collection, which arranges 31 songs around themes of deep romantic loss and subsequent grief. Read my analysis of Swift’s album (to read my song-by-song review of The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology—the most in-depth article I’ve written about a single work of music— become a paid subscriber). For weeks, Taylor Swift’s storybook album has been like a salve. Consequently, these reviews are some of my most intimate writing.

I’m discovering meaningful lessons while tending to my grief.

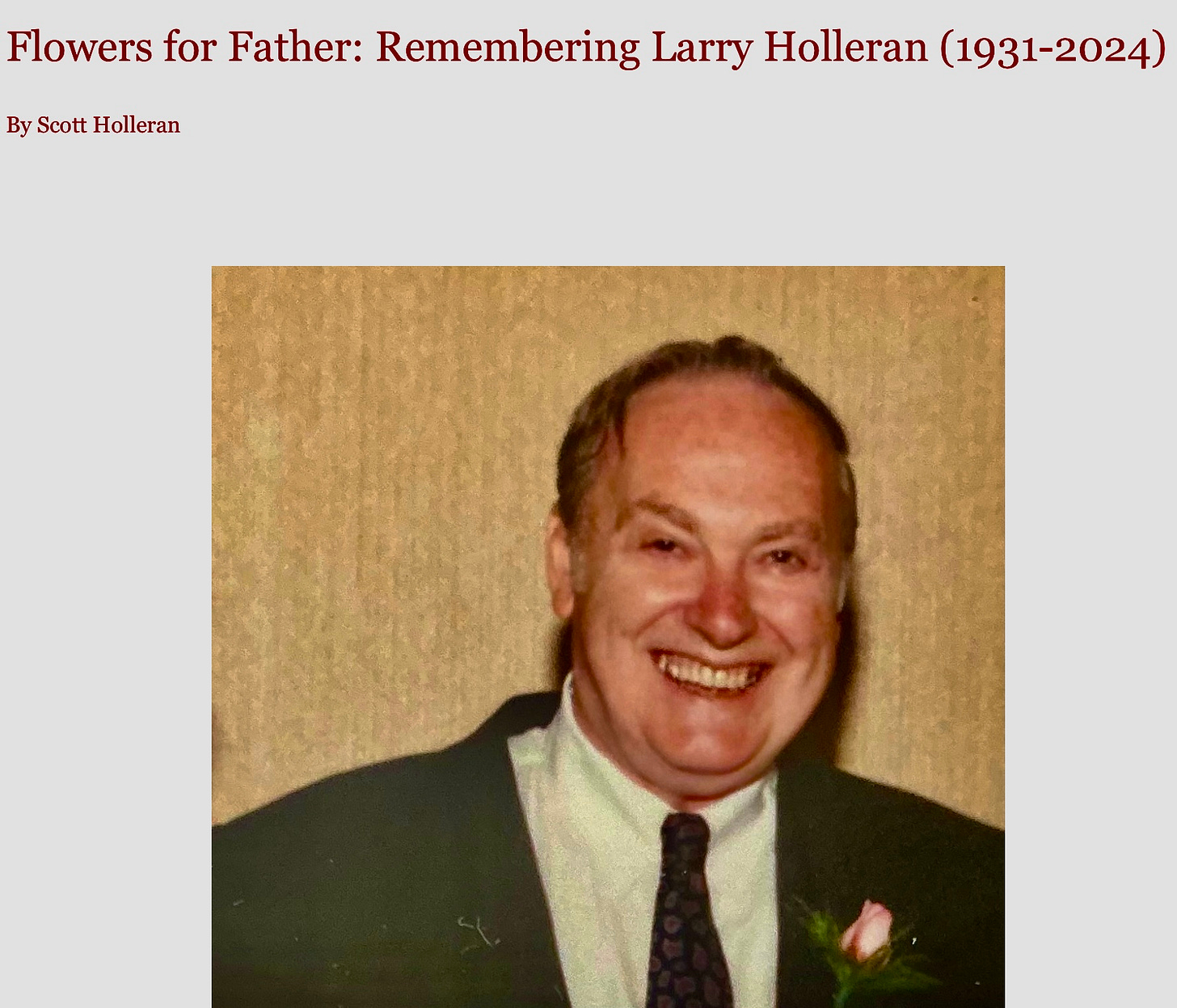

Father’s Day marks a milestone in my grief recovery. I’m not at liberty to go into detail, though I’m accepting a token for making progress and I am pleased to announce today’s publication of an article in Classic Chicago about me and my dad. My editor, Judy Bross, a decent, sensitive and artistic soul who is one of the most empathetic people I’ve worked with, encouraged me to write the essay, titled “Flowers for Father.” The article’s title contains a double meaning. So does its theme. I recount the story of bringing flowers to my dad at his office in a Chicago skyscraper. The occasion was the last Father’s Day in Chicago before moving to California. Now that my father has died, I’m unable to bring him flowers. This article will have to do.

“Flowers for Father” recalls our adult lives. Some of those times literally put us on top of the world—after climbing mountains in Switzerland, on an island off the African coast and in Southern California’s desert—invoking memories of trains and trolleys, inclines and skyscrapers in Chicago, Pittsburgh and San Francisco. Remembrance ties into unspoken trauma my father never discussed and occasionally let me glimpse, from expressing his thoughts on war, combat, killing the enemy and fallen comrades under his command to being wounded and facing imminent death. One of the gateways into my dad’s world is a novel which moved me—and inspired my favorite writer—in a way that’s fundamental to my becoming a writer. The novel is Ninety-Three. The author is Victor Hugo, favorite author of my favorite author, Ayn Rand. My father died at the age of 93, which figures into the story I’ve chosen to tell.

To grieve is to love, writes Megan Devine, author of the book I plan to review. Devine offers a new philosophy of grief which doesn’t reduce the individual to a blank piece of flesh mindlessly programmed to force a smile and “be positive.” I’ve learned that grieving the loss of someone—and that which—I love entails coping with the trauma of losing an irreplaceable (or prospectively irreplaceable) value. Grief’s not something to fix, eradicate, heal, move past or get over, according to Devine. I think it’s a portal to owning and honoring the self; so I aim to grieve with purity and clarity in sadness and love. If you’ve read this far, you probably know that grief, like life, goes on. May my articles on songs about lost love and a tale of life with my father help you grieve what you’ve lost or wanted and might’ve made—and might yet make—possible.

I can’t control whether there is more grief to come. It’s coming, whether I’m ready or not. To a certain degree, I can control whether I choose to learn, grow and recover through grief. This is my Father’s Day goal.

Related Articles and Links

Music Review: The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology

Taylor Swift’s April 19, 2024 album, The Tortured Poets Department, is like a muted storybook. With incisive lyrics, the moody, electronic album about losing a loved one—including losing the loved one—contains 31 thought-provoking songs.

Book Review: Attached

Reading Attached—a short, 2011 self-help reading divergence—gives me romantic love clues. This honest book hinges upon a psychological idea formulated in the 1950s called attachment theory. It’s based upon a test of toddlers entering a playroom with other toddlers. Each child is accompanied by the mother.

Music Review: Taylor Swift

Taylor Swift crafted her April 19, 2024 album, The Tortured Poets Department, to evoke powerful emotions. This musical storybook in black and white with Roman numerals unfolds in a variety of styles, from spaghetti Western score to a dreamlike aura in synthesized or machine-based music. The muted meaning of the story becomes clear.

Hi Scott,

You write with such power yet with tenderness, unafraid to hide the love in your soul. What a beautiful piece about your dad and your relationship with him.

All relationships are complicated and none more that the patent and child. I lost my mother in 2023; she was 91: a contemporary of your dad in many ways. She, however, lived a quiet life, was religious but not too much, and she even found Atlas Shrugged to be an interesting read when I gave her a hardback version of it.

She and I would talk almost every week, usually on Sunday. I miss those talks, and I always will.

I’m sorry for your loss, but that’s OK. It means you loved and are human. And that’s good.

Very best,

Mark