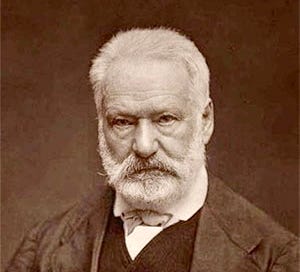

Today marks Victor Hugo’s birthday, which gives me reason to renew my pledge to read and re-read his writing and study his works of art—his poetry, plays and novels and sketches—and draw strength and joy. Hugo is the primary literary influence on my favorite writer, Ayn Rand. As Rand’s biographer, Shoshana Milgram, a scholar of Hugo’s work, observes in Essays on Ayn Rand's We the Living, throughout her career, Rand “quotes [Hugo] more than she quotes any artist other than herself.”

“What Ayn Rand loved about Victor Hugo,” Dr. Milgram writes, “when she discovered him in her early teens, was that he made ‘everything important and he feature[d] that which is dramatic and important,’ that she found in him ‘the grandeur of man and the focus on man,’ that his drama was ‘magnificent.’ She felt, she said, that Les Misérables was so ‘grand scale that I became almost possessive about that book’ and thought of ‘anything from Les Misérables, whether the name Jean Valjean or Gavroche or any of the …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Autonomia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.