Series Review: The Andy Griffith Show (CBS)

1960-1968 comedy with Don Knotts, Frances Bavier, Ronny Howard and Andy Griffith

For eight seasons, this show about a widower and his only child topped ratings and audience share on the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS). The Andy Griffith Show features the talents of its star, who’d triumphed on stage and silver screen. The comedy, centering upon a justice and officer of the peace, his son, a neurotic deputy and a maternal spinster, featured a fine supporting cast. This underestimated program captures the fade—and, at its best, the climax—of television’s golden age.

The Flaws

At its worst, The Andy Griffith Show, which debuted this month in 1960, ending with a final mid-September episode (launching its successor, the substandard Mayberry, RFD) in 1968, promoted Puritanism, traditionalism and selflessness, especially with the last episode’s stereotypical Italian familialism. Created by Sheldon Leonard, produced by Danny Thomas, with a signature opening sequence and whistling theme song, The Andy Griffith Show tends to conform to the status quo.

For example, Sheriff Andy Taylor’s (Griffith) later season fatherly advice, guidance and counsel about sex being for the purpose of procreation—which is essentially what he tells his son, Opie, without being explicit—is wrong. There’s no evidence by that episode that Andy’s capable of explaining sex as a sublime expression and culmination of romantic love—even as a natural, biological part of being human—let alone that he’s grown as a father. His child, Opie (Ron Howard, American Graffiti), knows about sex anyway. But Opie doesn’t want to spoil the experience for his dad, which is somewhat humorous, if out of character and out of alignment with the rest of Opie’s responses in the episode, as Opie goes door-to-door seeking a parent for an orphan. The episode, featuring Jack Nicholson (Five Easy Pieces) in another bad acting performance, demonstrates once again that Opie’s badly influenced by a friend or supposed friend. Opie’s judgment never improves throughout the series. Too often, Opie acts to please others, which doesn’t bode well for the rest of his life. Philosophically, the fifth season’s final episode, driven by Jerry Van Dyke’s flat, shallow humor, is among the worst as Sheriff Taylor censors a carnival act based on his aversion to (or fear of) sex.

The show’s worst episode depicts a town statue. The figure’s a legendary Taylor blood relative. Here, both Aunt Bea and Andy Taylor explicitly choose deceit—with the complicity of townspeople—in concealing that the presumed hero is, in fact, a swindler and total fraud who dishonors the fictional town of Mayberry. This destroys the series’ premise of Mayberry as charming. The whole episode amounts to rationalizing a morally corrupt ancestor for the sake of preserving facade and appeasing conformity; the ends justify the means. Even as presented in the episode, it’s morally bad. Given the show’s recreation of reality, it’s barely plausible.

Except that Mayberry’s residents do emerge during the course of the series as small-minded. This is on display time and again, prominently in “Howard the Comedian,” the 27th episode of the seventh season, which aired in 1967, featuring Andy watching a not-quite Lonesome Rhodes-type bumpkin—a callback to Griffith’s breathtaking performance as Rhodes in Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd, complete with baton-twirling.

Besides Andy Griffith and his insightful, comedic portrayal of singlehood, widowhood and fatherhood, the series’ strongest asset is the outstanding work of comedian and actor Don Knotts as Andy Taylor’s deputy Barney Fife (a blood relation is minimized). The show’s comedy is frequently too broad, which comes at the Barney character’s expense. This stifles the actor’s ability. Don Knotts is still hilarious.

The Andy Griffith Show stands out in spite of the flaws.

The Dance

The dance episode is an exquisite example. This story, broadcast during the sixth season, lightly dramatizes the shame and self-denial that can come from bad parenting and overly simple methods of coping. The dance episode shows the major characters at this point in the series—Andy, Opie and Aunt Bea Taylor (Frances Bavier), as well as schoolteacher Helen Crump (Aneta Corsaut)—at their best.

Here, Opie appears as a happy, playful and growing boy on the verge of pre-manhood who enjoys his friendship with Johnny Paul. He’s excited about a school party at the beginning of the episode, until he learns from Johnny Paul that the party will also include a dance. Previously, it’s been shown that Opie had been mocked and laughed at—really, humiliated—for his awkward dancing, which Johnny Paul reasserts. Accordingly, Opie mopes and decides not to attend the party.

Andy, Opie’s father, whom the audience learns had also struggled as a boy and was similarly mocked and made fun of by Floyd the barber and Goober the mechanic, struggles with the dilemma of whether and how to persuade his son to reconsider and attend the dance. Andy does everything but force his son, which he never does, to attend the dance. The father makes it clear that he wants Opie to attend the dance, and he comes up with the idea to have Aunt Bea teach Opie how to dance.

To her credit, Bea happily accepts the assignment. Throughout the episode, she demonstrates that she thinks boys ought to learn how to dance. It’s a value, she holds, and she recalls a young man who had been similarly ashamed, and that this may have retarded or adversely affected his growth, progress and development as a man. Andy’s girlfriend, Helen, too, encourages the idea that boys ought to learn how to dance (Helen’s the one who chose to make the party a dance). She asks Andy to chaperone the dance, which he agrees to do. Opie does agree to attend the dance, though he’s reluctant to step out and dance, despite (or perhaps intimidated by) his peers’ freestyle dancing. Andy goes to talk with his son, though the matter remains unresolved.

Crucially, Helen Crump, the teacher, approaches Andy while he’s talking to his son; Helen, breaching custom, protocol and tradition, asks Andy to dance, stressing to Andy that he ought to set an example for his son, underscoring the implication that he ought not to ask his son to do something that he himself is not willing to do.

Reluctantly and awkwardly, Andy agrees to dance with Helen in a go-go or frug style of mid-Sixties modern dance. The kids stand back and cheer for their teacher and the town sheriff to dance—showing social acceptance of Andy while acknowledging his awkwardness—and Opie starts to accept and laugh along at his dad dancing with his teacher. Soon, Opie summons the courage to ask someone else to dance, which, when a girl accepts the invitation, happens. Father and son dance in proximity to one another, laughing while dancing with their partners. Father and son return home in the last scene of the episode with Aunt Bea knowingly looking at Andy as Opie and Andy recount their mutual joy in dancing.

The dance episode dramatizes that Andy struggles with fatherhood, making himself vulnerable, which lets him fix (or address) a flaw as a byproduct of his efforts to be a good father. The episode also shows Helen’s moral courage in standing up to her mate—for the sake of the pedagogical principle she holds. Aunt Bea, too, continues to assert the importance of the opposite sex learning to master the art of dancing. Or at least improve. Of course, Opie shows courage as well. He chooses to step up and dance. Exercising his own free will—under parental guidance, not compulsion—Opie dances on his terms. Not to please others, including, and, in particular, his dad. Everyone wins, makes progress and, in body and mind, feels and does something good.

Seasons

After first season exposition and set-up—an episode about the proper way to think of charity is the inaugural season’s best—The Andy Griffith Show gets going in earnest with Aunt Bea’s wedding bell blues in a touching, beautifully written episode about romantic love and the meaning of family. Amid the folksy, front porch guitar-strumming and singing, Andy Taylor emerges as a man of moral integrity. Everyone smokes cigarettes in these early Sixties seasons—fictional Mayberry’s in tobacco-rich North Carolina, after all—which include an intelligent vaccine-themed episode.

Gomer Pyle, a silly gas station attendant character played by Jim Nabors, and schoolteacher Helen Crump come into play during the third season, which introduces a hillbilly family named the Darlings (Denver Pyle, among others), in the first of several humorous appearances. Season three introduces an elusive, wild-eyed character known as Ernest T. Bass (Howard Morris).

Following the assassination of President Kennedy, the fourth season is more somber in tone. This marks a series turning point as Gomer Pyle’s character begins to replace Barney Fife’s as the humorous foil, accelerating the show’s dumbing down; Pyle becomes a stronger presence—including references when he doesn’t appear in an episode—as Pyle joins the U.S. Marine Corps in a tease of a spinoff’s pilot. Sadly, Barney’s character gets dumber, too, rather than grow in confidence. Andy Taylor placates and deceives to spare Barney’s pseudo self-esteem. Thanks to Knotts’s performances, Barney Fife is capable of being more layered and interesting than the moronic Pyle; episodes with both characters do not mesh or play well.

In season five, with the same opening segment, Knotts as Barney still provides moral lessons with fine, physical comedy, though Knotts felt underestimated and eventually left the series. Allan Melvin memorably portrays a grocery clerk named Fred, whom deputy sheriff Fife repeatedly warns to cease sweeping trash into the street. This is the episode in which Barney’s martial arts lessons are at issue; this time, however, rather than enlist everyone to fake reality and go along with deceit, Andy encourages Barney to have courage by appealing to Barney’s fidelity to upholding the law. In this and other episodes, one senses possibilities in Barney, who is often sharp with forethought in his own way, as when he ventures an opinion about the evolving teacher-pupil relationship. Making and keeping Barney Fife ineffectual hurt the show.

The most problematic character, Ronny Howard’s Opie, grows in body, though not with consistency in character or virtue (as late as the seventh season, Opie misbehaves based on bad influences). With a crush on his dad’s girlfriend, teacher Helen Crump, in the fifth season, Opie grows taller and thinner and his voice changes. Andy, who serenades Helen on the front porch with his guitar and singing, gradually grows more romantic during the series and Andy Griffith delivers a great, soulful performance in the 1965 episode “A Guest in the House”. The fifth season includes carnival-themed episodes and references to the then-newly emergent professional football, a brutal sport which came to dominate the nation’s culture, and Cary Grant movies. Classroom scenes featuring displays of mid-20th century education are evidence that young Americans once studied history—with a portrait of George Washington and a cut-out of the Mayflower—offering a severe cultural contrast.

The black and white show’s first color episode aired as the opener of the sixth season with Andy Taylor as an angry, miserable and unhappy dad to his son, providing proof that, as U.S. technology improves, the quality of the nation’s arts and culture often deteriorates in direct proportion. Opie gets praised as a man by the end of the story—for sacrificing his job, which he gets and earns while trying to make money to pay for fixing his bicycle—for practicing an act of altruism by letting another person have the job based on need. By then, a new deputy character has replaced Don Knotts’s character—another moron character was added to the cast—with no exposition about what happened to Barney Fife (Knotts left for other opportunities). There’s not a single mention of Barney in this season.

A four-part episode arc, “The Taylors in Hollywood,” dates the show. Opie refers to John Wayne and Elvis Presley. The Taylor family departs Mayberry, which still has dirt roads, via a Trans World Airlines (TWA) passenger jet. With a nod to getting Doris Day and Rock Hudson autographs, Opie’s depicted describing an outfit as “sissy” and remarking to his dad, “hey Pa, there goes another grown-up lady in trousers…” Andy Taylor still seems angry and lonely.

Hope Summers co-stars throughout the series as petty, shallow Clara; in this season, Clara has one of her few finer moments singing “Some Enchanted Evening” from Rodgers’ and Hammerstein’s South Pacific. Music is integral in The Andy Griffith Show, from Andy’s songs to the Darlings’ banjo and jug band. When Barney returns for a Mayberry Union High reunion, only to find his ex-girlfriend Thelma Lou (Betty Lynn) married, he harmonizes with Andy, and, in his final guest episodes as Barney, Don Knotts showcases his acting range. Driving a baby blue convertible that backfires—wearing his signature suit—Barney Fife makes a graceful exit from the series.

By the seventh season, the series winds down as Opie and Andy engage in a battle of the sexes in an interesting, thoughtful story of best practices and being magnanimous. A baseball game and newspaper column by Howard Sprague (Jack Dodson), one of the newer, later series characters, explores the meaning of being objective (Ron Howard’s brother and frequent future player, Rance Howard, wrote the episode).

Rudyard Kipling’s If— merits a reference in the first episode of the eighth and final season of The Andy Griffith Show. With plots about teamwork (in a bowling-themed episode) and a vacation in Mexico—with Floyd’s barber shop replaced by Emmet’s machine repair shop—and Aunt Bea’s rival Clara’s final redemption, which is stagy if one of the better parenting fables, the final season takes risks and ties up loose ends.

Among the highlights: Aunt Bea as a swinger lets loose—she also trains as an aviation pilot in a tale that’s not as preposterous as it seems—Howard embraces being a bachelor after his overbearing mother gets married and moves out—Helen’s hidden past looms—and an episode revolving around Gomer Pyle’s cousin Goober’s abilities is also good. In this episode, Goober learns from Opie after both of them read a magazine article about a CEO who lost $17 million after inheriting a company; there’s weak exposition but a solid theme.

From there, a farmer character known as Sam Jones (Ken Berry), is introduced as the Mayberry resident recruited by Goober, Howard and Andy to run against Emmet the repairman for town council on the grounds that Sam’s not a politician. Sam has a brief front porch conversation with Andy after experiencing pre- and post-election influence peddling. Andy passes the torch at twilight for Sam to lead the town.

In one of the show’s best episodes, Goober tries computer dating—encouraged by Sam and Andy—and gets what he wants. He learns to read Aristotle. He gains self-confidence. This marks Ron Howard’s final series appearance as Opie.

The Guest Cast

Among The Andy Griffith Show’s guest actors:

Elinor Donahue (memorable as the first born child in Father Knows Best) as Ellie, Mayberry’s druggist and Andy’s occasional girlfriend in the first season

John Dehner (who, like Denver Pyle, went on to co-star in various incarnations of The Doris Day Show) in the third season

Gavin Macleod (Murray Slaughter in The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Captain Stubing in The Love Boat), comedian Don Rickles as a loser with Andy pitching optimism and Larry Hovis (Hogan’s Heroes) in the fifth season

William Christopher (Father Mulcahy on the Korean War comedy MASH) as an income tax collector in season six

Jack Nicholson (re-appearing in the final season as Bea Taylor serves on a jury) in the seventh season

In the final season, guest actors include Harry Dean Stanton, Teri Garr (Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Tootsie), Jack Albertson (Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory) as cousin Bradford, Jack Bannon (Lou Grant) as the broadcaster who introduces Aunt Bea’s televised cooking show, Rob Reiner (hippie leftist Meathead on All in the Family) and Whitney Blake (Hazel) as a lady lawyer from Raleigh in an episode in which Andy, once again, is tested and deceives Helen

Conclusions

Reflecting the culture, The Andy Griffith Show mixes platitudes with good concepts, themes and comedy. Pioneering unseen characters with unheard voices—before other distinctive TV characters, such as Carlton the doorman on Rhoda—this CBS comedy displayed humor via unseen characters Juanita (a waitress having casual sex or an affair with Barney) and Sara, Mayberry’s nosy telephone operator.

The Complete Directory to Primetime Network and Cable TV Shows (49th edition: 1946 to Present) by Tim Brooks and Earl Marsh, indexes The Andy Griffith Show (October 3, 1960 to September 16, 1968) as having usually aired at 8:30pm, 9pm or 9:30pm.

The authors chronicle that:

The small town of Mayberry, North Carolina is the setting of this highly successful, homespun situation comedy. Sheriff Andy Taylor was a widower with a young son, Opie. They lived with Andy’s Aunt Bea, a combination housekeeper and foster mother for Opie. Andy’s deputy was his cousin, Barney Fife, the most inept, hypertense, deputy sheriff ever seen on television. The tone of the show was very gentle, giving Andy the opportunity to state and practice his understanding, philosophical outlook on life…[o]n the first episode of Mayberry, RFD, the successor to The Andy Griffith Show, Andy and Helen married and moved away, leaving the supporting cast to carry on with the new star, Ken Berry, in the role of Sam Jones—another widower with a young son.”

Reruns are popular. A “nostalgic reunion of the series’ original cast,” Return to Mayberry (broadcast in April 1986), is the highest-rated movie of the 1985-1986 season. Don Knotts, who’d starred on a top-rated ABC comedy and played a vital role in the motion picture Pleasantville, reprised his deputy sheriff role.

I think the series’ commercial and creative success stems from characters and plots that express the best of young America’s sense of life—in music, mythology and meaning—though there’s something more. The Andy Griffith Show emphasizes moral courage. In every endeavor and pursuit, whether a headstrong female pharmacist, an innocent motherless child, a honest alcoholic, a bum with a sense of decency, an armed and dangerous criminal—or a homely cousin, ignorant mountain men or an older, unmarried, childless woman—living a better, happier life is the ultimate point.

Guided by an affable man who’s also the town’s policeman and moral compass, who has his own hidden, dark, unspoken past—a wife and mother who died—everyone worth watching strives to learn, improve and become better, worldly and efficacious. The series succumbed to today’s rot, giving way to commonly accepted notions that hasten the world’s demise. It is too folksy, though it is mostly, merely too plain, at times with rotten ideas seeded into its screenwriting.

The Andy Griffith Show—like its heirs, such as Valerie, Little House on the Prairie, The Rockford Files, The Waltons, Schitt’s Creek and Barney Miller among others—comforts and soothes as it ties humor into everyday situations with flawed, ordinary folks. The result provides examples of strong, moral absolutes amid dark, complex challenges.

Barney, Helen and Opie endure not because they’re weak or inconsistent but because they are innocent, strong and resilient. Characters also linger for their optimism, productiveness and warmth. Aunt Bea’s awful pickles and her nephew’s sparing her unnecessary embarrassment—even when he’s wrong to do so—Goober’s self-education, Otis the drunkard making himself presentable, Ernest T. Bass going on a rampage, saucy ladies seducing policemen, and Andy doing his best to raise a family, uphold the law and, eventually, find love and romance again—this eight-year depiction of undaunted small town American lives brews and stirs for a reason. Going fishing with your dad—or for a drive down a country road—can afford rich rewards. Knowing that decent people exist, whether they’re pumping gas, delivering justice, baking pies, playing baseball, serving hot meals or letting you pass through town—or stay for a while—illuminates and affirms the wider world.

It’s not that Mayberry is ideal. It is not. Andy Taylor and his loved ones—broadcast during trying, climactic times—came off as real, true and, at best, honorable. The Andy Griffith Show mirrors the goodness of a conscious and knowing, and rural, way of life.

Related Articles

Series Review: Frasier (Paramount Plus)

With affection for NBC’s Frasier, one of television’s best romantic-realist comedies, I watched five episodes of the new streaming TV series by the same title from Paramount Plus. This affinity for the original 11-season program (based on the Frasier Crane, MD, character played by Kelsey Grammer created for and spun off from NBC’s

Series Review: Tucker Carlson Today on Fox Nation

Tucker Carlson’s been around for decades. I remember watching him for the first time years ago on cable news when he was a bow-tied, conservative pundit. As I recall, he’s hosted his own program on all three major cable news stations, Microsoft’s channel with NBC News, MSNBC, Fox News Channel (FNC) and Cable News Network (CNN). This month, he started ho…

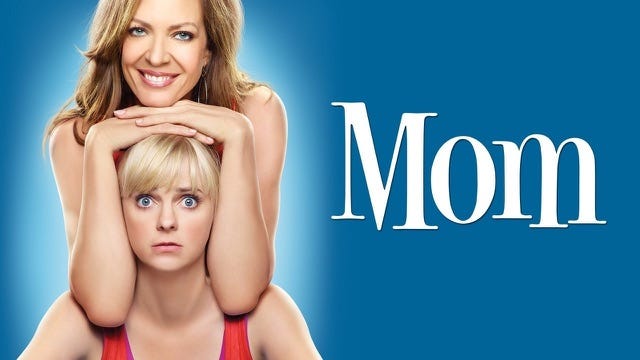

Series Review: Mom (CBS)

As long as you know what you’re in for, Mom, which ran for eight seasons on CBS and gains thematic momentum in the fourth season, is filled with laughter and love. Though all seasons are worth watching—ideally, from the beginning—this is a mildly biting, not romantic, let alone heroic, television comedy series. With a lifelong personal history of drug and alcohol addiction—an affliction suffered by loved ones, though not by me—I can appreciate Chuck Lorre’s dark, alcoholic-themed humor.