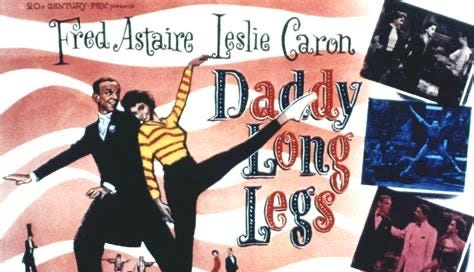

Later in his motion picture musical career, Fred Astaire made a movie with a young French actress and ballet dancer. I watched Daddy Long Legs for the first time. I find it perfectly charming. Apparently, the film has a mixed or bad reputation among predominant critics. Unsurprisingly, I reached the opposite conclusion.

Besides Mr. Astaire, who co-directs and choreographs Daddy Long Legs’s dance, director Jean Negulesco deserves credit. In this beautifully crafted two-hour film, he integrates disparate elements of street or freestyle, ballet, ballroom, jazz and modern dance, storytelling, drama, comedy and special effects. Mr. Negulesco strokes and blends them into a seamless moving picture. The result yields a lightness which is at once innocent, forbidden and emotional. Daddy Long Legs endures—against its detractors’ claims—to express pure delight.

It is, in essence, the story of two lost souls; it’s you and me against the world. He’s an older man (Fred Astaire in his mid-50s) and she…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Autonomia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.