I attended the opening this spring of a new exhibit at the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh’s strip district. An “immersive walk-through” of American labor artist John Kane’s “Crossing the Junction” oil painting purports to let visitors travel Pittsburgh’s topography as Kane did and explore his artistic process.

It doesn’t, of course, because Kane’s painting is a painting. He created it as a painting and it ought to be experienced as a painting—not chiefly as an artifice of Western Pennsylvania’s landscape—and the Smithsonian Institution-affiliated history center offers a misconceived jumble of leftist politics which sugarcoats a self-taught artist’s abuse, alcoholism and attempted suicide. It’s nevertheless an interesting experience.

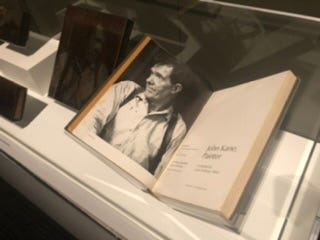

The exhibit is based on what’s touted as new scholarship by Louise Lippincott and Maxwell King, authors of American Workman: The Life and Art of John Kane, and the Heinz History Center exhibition features 37 of …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Autonomia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.