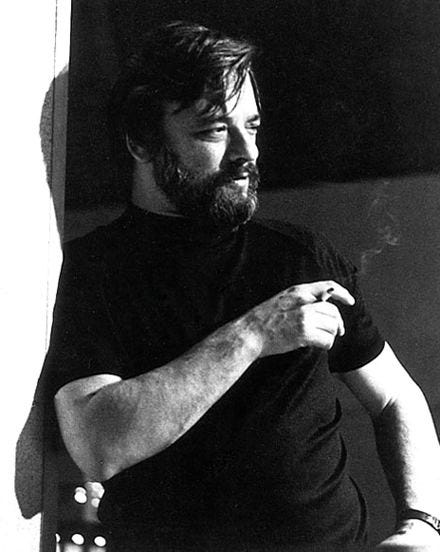

Writer Stephen Sondheim died at his home in New England this week. He was 91 years old. The Broadway lyricist for West Side Story was also the composer for Into the Woods and he’s best known for a frequently covered song, “Send in the Clowns”, from his musical A Little Night Music. Sondheim wrote many other works of musical theater, including Company, Assassins and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

Stephen Sondheim took topical, lyrical and musical risks throughout his career. He ended up working with some of the greatest artists of his time, including his mentor, Oscar Hammerstein, who was his childhood neighbor. His themes were dark, bloody and pained and they were rarely light, cheerful and gay. But it’s wrong to say (as many do) that he changed musical theater in some fundamental way. I think he added to it.

Today’s dominant intellectuals lie. They act as though musical theater was frivolous and unserious before Sondheim. It wasn’t. Much of what they created, and espec…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Autonomia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.