Can the ordinary man make extraordinary impact? The answer lies in the life and career of Gene Hackman, a United States Marine born here in Southern California—in one of our poorest counties—in San Bernardino in 1930. Hackman’s career spans decades. He’s not a movie star. He’s not known for playing the hero—Gene Hackman often played the villain—and he’s not known for showboating. Gene Hackman is an actor, not a celebrity.

Acting was his way of life. Hackman died at the age of 95 at his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico. This, too, affirms his impact on American culture. Hackman’s way of living—in solitude and self-reliance, peace, quiet, in love with his wife, who was also found dead with a dog in their home—dovetails into an ending from one of his movies.

This article recaps his career, taking liberty to trace his films to my life and career. I’ll quote an excellent actor and movie critic for a top news magazine, as well as an excellent actress, to express Gene Hackman’s defining qualities. The mysterious circumstances in which he died tie into his legacy. I’ll answer the opening question.

Gene Hackman’s Films

Beginning in the early Sixties, when Hollywood started rejecting glamor, romanticism and gorgeous movie stars—which decimated the movies, culminating in the late Sixties—Gene Hackman cashed in on the push for plain actors, i.e., Dustin Hoffman, Jack Nicholson, Al Pacino. According to film critic and historian David Thomson in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film (fifth edition)

…Hackman had established himself as an interesting character actor, capable of grainy authenticity. From the stage, he made a film debut as the grating small town husband in Lilith (1963) and, after A Covenant with Death (1966), Hawaii (1966; [adapted from James Michener’s novel] by director George Roy Hill) First to Fight (1967) and Banning (1967), he played Clyde’s older but junior brother in Bonnie and Clyde (1967).…”

In that last film, co-written by Robert Benton, Gene Hackman’s performance as the criminal brother who’s killed, pivots the plot. By 1969, Hackman appeared in a few downbeat, anti-heroic movies: The Gypsy Moths directed by John Frankenheimer, Downhill Racer directed by Michael Ritchie starring Robert Redford and Marooned. In 1970, he delivered a powerful leading performance in I Never Sang for My Father, directed by Gilbert Cates, who went on to direct the Oscars telecast for decades.

Hackman played a tough cop in the car chase-action movie The French Connection in 1971. In The Poseidon Adventure, he played a post-Vatican 2 priest leading a capsized ocean liner’s passengers to safety. Two years later, he was leading actor in Francis Ford Coppola’s forewarning against the surveillance state, The Conversation, and he appeared in Mel Brooks’s farce Young Frankenstein. I first saw him on the silver screen in 1975 as a cynical private detective in Arthur Penn’s Night Moves. He reprised his role in a sequel to The French Connection—this time as a heroin addict—and I saw him that same year in the lightly anti-Western romp Bite the Bullet directed by Richard Brooks. Hackman’s only 1975 movie I didn’t see in theaters co-starred Burt Reynolds and Liza Minnelli—Lucky Lady, a Prohibition-themed comedy directed by Stanley Donen (Singin’ in the Rain)—which debuted (and bombed) on Christmas Day.

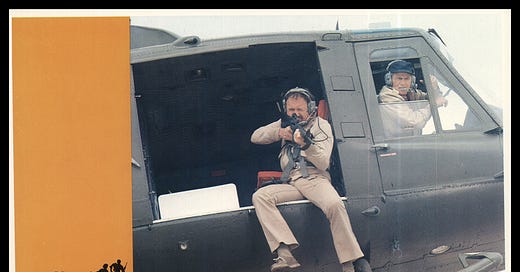

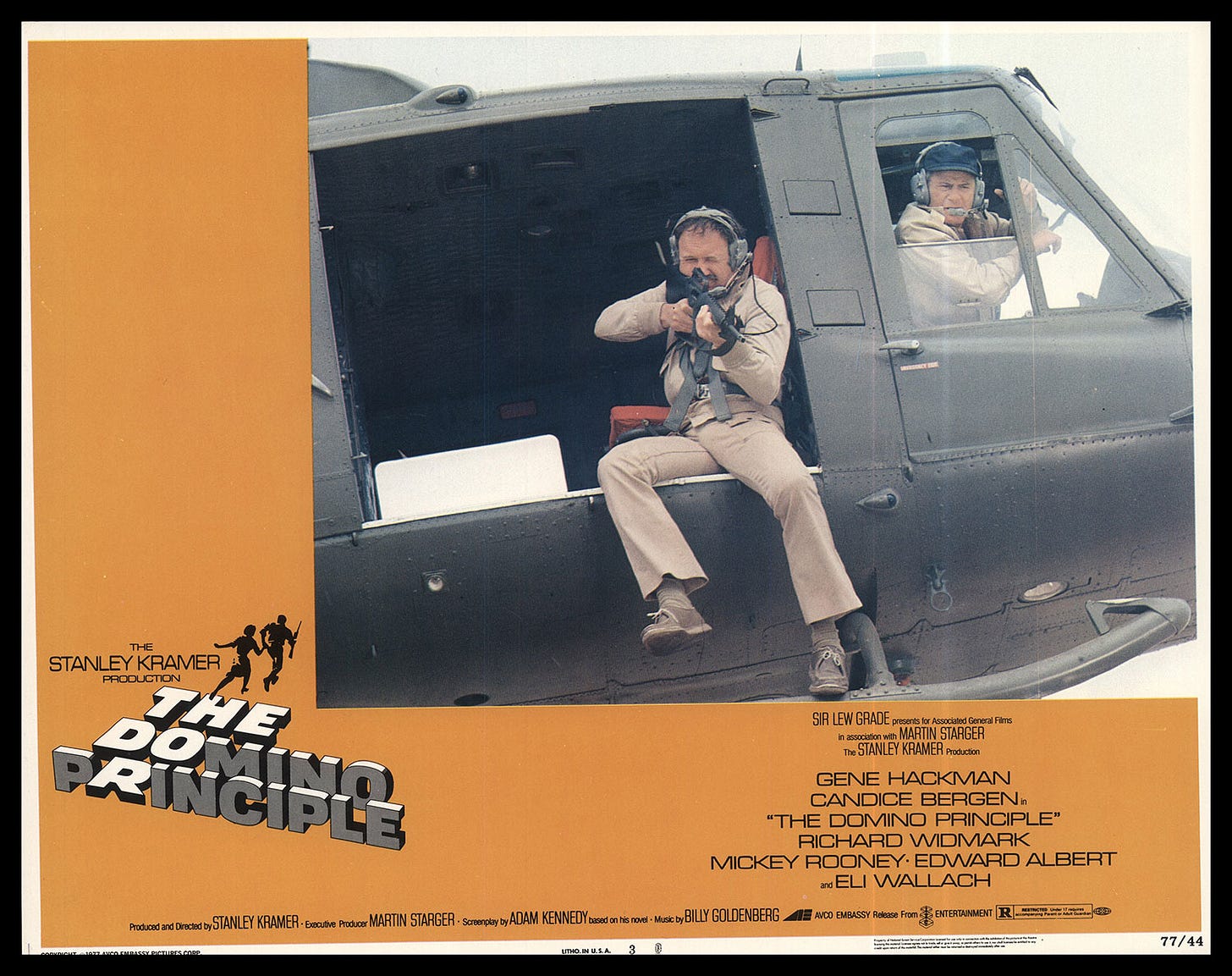

As a boy, I went to see all three of his 1977 films in theaters with my war veteran dad: March or Die, a miserable, French Foreign Legion-themed film about the aftermath of the Great War (World War One); a foul conspiracy-themed Vietnam War-era film, The Domino Principle (more on this later) and Richard Attenborough’s adaptation of Cornelius Ryan’s World War Two epic, A Bridge Too Far. These films were mediocre at best. Hackman was not. He portrayed comic book villain Lex Luthor in Richard Donner’s romantic yet overestimated Superman in 1978 and reprised the role for years, adding humor. I saw that in theaters, too, impressed by his ability to play down.

Appearing in the first of many of Warren Beatty’s flops—the romantic Communist movie, Reds—in 1981, he followed up as the uncredited voice of God in a comedy I was excited to see in theaters—Two of a Kind co-starring John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John—and a string of serious-themed films in the Eighties: as a secretary of defense in Kevin Costner’s breakout film, No Way Out, Uncommon Valor, Hoosiers and Alan Parker’s Mississippi Burning.

The Nineties were Hackman’s swan song. Gene Hackman appeared or co-starred in Clint Eastwood’s 1992 inscrutable anti-Western Unforgiven, Sydney Pollack’s adaptation of John Grisham’s novel The Firm in 1993, Wyatt Earp in 1994, director Sam Raimi’s underestimated The Quick and the Dead in 1995, hamming it up in Tony Scott’s submarine thriller Crimson Tide in 1995, downplaying again as a bewildered conservative politician in 1996’s adaptation by Mike Nichols of La Cage Aux Folles, The Birdcage, starring Robin Williams and Nathan Lane, Extreme Measures in 1996, reuniting with Clint Eastwood for his adaptation of a political novel in Absolute Power in 1997, a reunion with Robert Benton for Twilight in 1998 and as the voice of General Mandible in Antz in 1998, the same year he co-starred in the interesting Enemy of the State. I saw most of those in theaters, too. In the 21st century, Hackman appears in Under Suspicion year 2000 and in Gore Verbinski’s dark but entertaining Brad Pitt-Julia Roberts vehicle, The Mexican, in 2001. That last movie’s the only one I reviewed for publication.

In retrospect, Hackman’s ordinariness aided his endurance as an actor. In a 1976 interview with Playboy, director Robert Altman refers to Hackman as a “non-star.” Playboy followed up by asking: “You mean you wouldn’t consider Hackman, who is asking $1 million or more a picture, a star?” Altman answers: “Not in the terms that [Paul] Newman and Robert Redford and Steve McQueen are. In any picture where he can be Steve McQueen, McQueen is worth his $3 million, because his pictures can be booked around the world and earn back the tab. Hackman is a fine actor, but I don’t believe he’s worth paying that kind of money, unless he’s in a very good picture. In a bad picture, he just goes down with the whole crew.”

Yet Hackman’s involvement could make or break a picture. According to author Patrick McGilligan’s unauthorized 1999 biography of Clint Eastwood, Hackman’s participation made Unforgiven possible:

The sheriff’s part called for an actor who could stand up to Clint. The script went out to Gene Hackman, widely regarded as a virtuoso star, although he was often reduced to second leads. Hackman, winner of an Oscar for his gritty performance in The French Connection, turned the part down, as he had once before, when Francis Ford Coppola had talked about it with him. Later, Hackman was candid in telling journalists that “I didn’t see what Clint saw in it at the time“, and that “I thought it was too violent“. His agent urged the actor to reconsider, and Clint was persuasive. Hackman’s involvement was crucial to the growing significance of the project.”

Warren Beatty, who did a scene with Gene Hackman in Robert Rossen’s 1963 movie, Lilith, finished the scene thinking, “this guy’s such a good actor, he’s making me look good.”

Gene Hackman also leads 1977’s dark, biting The Domino Principle, directed and produced by Stanley Kramer. In the convoluted film featuring Mickey Rooney, Candice Bergen, Richard Widmark, Edward Albert and Eli Wallach, with an adapted screenplay by Adam Kennedy from his novel, Hackman portrays a Vietnam War sniper drawn into an assassination plot. Though the movie tanked at the box office—me and my dad were among the few people seeing it on opening weekend—the movie broke even. Hackman, who wrote fiction after retiring from acting, admitted that he “didn’t understand it either.”

Hackman’s essence

Actress Viola Davis remembered Hackman, posting on social media: “Loved you in everything! The Conversation, The French Connection, The Poseidon Adventure, Unforgiven—tough yet vulnerable. You were one of the greats. God bless those who loved you. Rest well, sir.” This sums up Hackman’s ability to shuttle between types.

As Time magazine film critic Stephanie Zacharek wrote when he died: “[Hackman] gravitated toward characters whose core of lies came wrapped in the truth, or the other way around. Either way, no matter what character he was playing, you had to keep an eye on him every millisecond, to detect infinitesimal shifts in tone or feeling, sleight-of-hand elisions.”

Zacharek and Davis grasp Hackman’s ability to convey varying, contrasting qualities. Hackman’s co-star in The Birdcage—their dinner table contest and chemistry powers the whole movie’s hilarious, farcical twist—Nathan Lane is deeper and more specific, writing that:

Gene Hackman was my favorite actor, as I think I told him every day we worked together on The Birdcage. Getting to watch him up close, it was easy to see why he was one of our greatest. You could never catch him acting. Simple and true, thoughtful and soulful, with just a hint of danger. He was as brilliant in comedy as he was in drama and thankfully his film legacy will live on forever. It was a tremendous privilege to get to share the screen with him and remains one of my fondest memories. Rest in peace, Mr. Hackman.”

The facts of Hackman’s death

At 95, Gene Hackman's pacemaker showed that he probably died at his home on February 17, according to police. Hackman’s German Shepherd, named Bear, was thought to have been found deceased, but it was later disclosed that Bear had survived, with a second dog named Nikita, according to Time. The dead dog found near Hackman’s wife Betsy Arakawa was named Zinna. The Hollywood Reporter wrote that “police found “the front door of the residence unsecured and opened, deputies observed a healthy dog running loose on the property, another healthy dog near the deceased female, a deceased dog laying 10-15 feet from the deceased female in a closet of the bathroom, the heater being moved, the pill bottle being opened and pills scattered next to the female, the male decedent being located in a separate room of the residence.”

Arakawa, Gene Hackman’s 64 year-old wife, died of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, which was confirmed by New Mexico’s chief medical investigator. Authorities estimate that Arakawa's death occurred around February 11—with Hackman estimated to have collapsed on February 17—and their bodies were discovered with Zinna the dog on February 26. Even in death, there was the sense of the ordinariness of daily life mixed with a deeper, nuanced and untold story.

I think this simplicity, named by Nathan Lane, in everyday acting by an Everyman making excellence in daily rituals, goes to why Gene Hackman, unlike more flamboyant peers trafficking in Hollywood’s post-Golden Age plainness and disturbing, disturbed movies, captures Gene Hackman’s way.

As Hackman once put it: “There is some quote that people live their lives trying to change the world to fit their own prejudices. That’s kind of interesting. We all do that to some extent. We make the world the way we want it to be.” Gene Hackman’s world was to elevate and embrace the ordinary and, in this, mine for the rarest and best.

Related links, articles and episodes

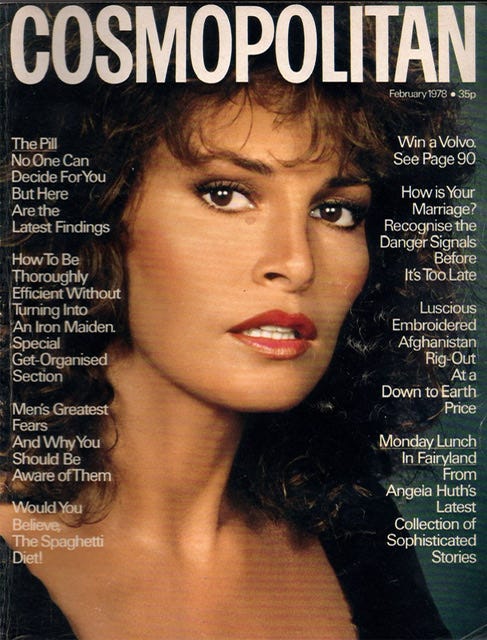

Obituary: Raquel Welch

The scope of Raquel Welch’s ability to entertain comes through if you think about it.

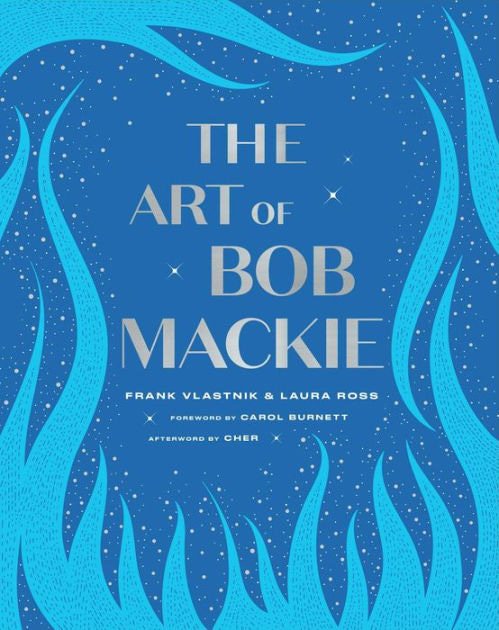

Book Review: The Art of Bob Mackie

Priced at $50 (the e-book at $17), Simon & Schuster’s large, 304-page book, The Art of Bob Mackie, with fore and afterwords by Carol Burnett and Cher, is the first complete, authorized collection of fashion designer Bob Mackie’s sketches, drawings and photographs. Everything is contained in a fabulous, full-color biographical volume. This is like a coffee table history of some of the best of Seventies pop culture.

Movies: “The Journey” (1959)

The Journey is uniquely interesting and thought-provoking. Directed by a man born in Kiev when the city was located in Soviet Russia, now in Ukraine (which was invaded by Russia three years ago today) and written by a man born in Hungary, the 1959 motion picture depicts a band of international travelers and tourists detained by Communists during the 1956 uprising of Hungarians in Budapest when Soviet Russia invaded. The film has been forgotten. Several factors make it worth watching.

Scott -

Lex! The French Connection! Tenenbaums! Such great roles. So many I need to still see.

Great tribute—well-researched and enriched by the personal memories you shared. It was a tragic end to a long life, but what a remarkable one it was! This actor touched so many, leaving behind an incredible legacy. I enjoyed catching this one from DDD after his passing:

https://youtu.be/bme-O5oEsXo?si=MYUGnkjcAhNB9Gz-&t=341