There’s not enough Superman in Superman. It’s a good movie—a modern film made for today’s audiences and all that this implies. If the comic book hero with his loyalty to truth, justice and the American way, unfortunately a phrase left out of this film by director James Gunn, is to have a future, this movie will be part of the reason. Despite its flaws, there’s plenty to appreciate and, occasionally, admire.

The story’s framed before the film begins as an animated logo featuring a man breaks free from his chains. This is a metaphor for the DC Comics-originated Warner Bros. motion picture. The movie begins at sunrise, the dawn of a new day. Automatons at the Fortress of Solitude and holographic parents with translucent blue eyes commence its exposition. Superman is a comic book movie. This is a live action comic strip which is important to remember.

The villain, Lex Luthor, played by Nicholas Hoult (the lead actor in last year’s best movie, Juror No. 2 by Clint Eastwood), gets too much screen time. Hoult’s good in the role, launching a convoluted plot to destroy Superman with an autocracy disguised as a corporation with government contracts and favoritism or cronyism and allegiant employees who don’t question, doubt or scrutinize his motivations or actions.

This is not an origin story. The context presumed by filmmakers is that you’re already versed in Superman mythology. The theme that vulnerability is a superpower—the relevant theme of author Brené Brown‘s work—strikes a powerful point. Journalist Lois Lane, the foil and true love of Superman‘s alter ego, journalist Clark Kent at the Daily Planet, poses ethical questions and demonstrates an ability to be objective. Lane is a compelling character which should’ve been larger like the Superman character. But she gets the point across, particularly in scenes taking place at her home in downtown Metropolis. It’s dominated by books on bookshelves. Not screens.

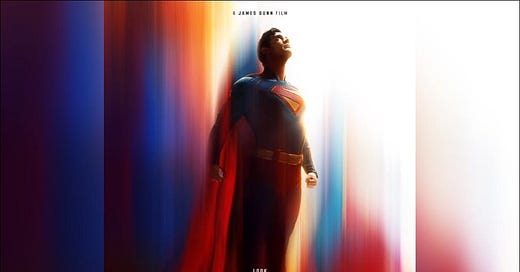

Lead actor David Corenswet playing Superman is talented, resembling Nineties leading actor Brendan Fraser. With references to sacrifice, grooming and humanity, as well as subtitles refreshingly displayed in a comic book font in all caps, the screen pops with something to watch and something to think about. Throughout Superman, Superman mines his mission to find, protect and rescue the good.

There’s nothing scarred, dark, sinister or foreboding about him. He’s bright. He’s decent. He’s intelligent. He’s possessed with power, and this gets a depth it rarely does in today’s movies. He bleeds, gets messed up and bruised and Superman hurts. Superman’s perfect. He not only remembers the individual’s name when he saves someone’s life—life is the ultimate standard of his values—he uses the individual’s name with passion and righteousness and he means it. It’s as if he names the individual to admonish you for not naming him. Superman’s not a cipher. Contrary to the woke dogma dominating our age, to Superman, life matters foremost, repudiating a populist slogan. This means his own, with egoism not as an afterthought, as conservatives and leftists preach and practice, but, thanks to his mid-American parents, as a forethought; himself matters foremost. He seeks a life of love, romantic and career passion, sex and happiness. That’s that.

Those parents in America’s Prairie State make Superman (and Superman) better and this is really the movie’s secondary point. The American hero as a self-made man—the archetypical individualist, non-conformist (witness end credits)—was made and forged and gilded in the middle of America—not by coastal college-bred cultists and not by forces in the South (this means Texas, too). Superman acts to defend Metropolis first and foremost. But when you meet his mom and dad—his real mom and dad in an explicit embrace of the self-made, adoptive family as against blood, tradition and high-brow, blueblood familialism—you learn why. As Ayn Rand wrote, man is a being of volitional consciousness; he must choose to think and this goes to the core of Superman. Superman’s intellect, integrity and vulnerability springs from his father whose face bears a lifetime of being committed to excellence in every endeavor, from harvesting a farm, loving a mate and raising a son who’s different with love, pride and the unabashed display of emotion. Being undaunted marks the Kent family credo.

A rascal of a dog named Krypto, mocking the substance that can take Superman down, adds a playfully undaunted dimension and so does the movie’s only other super-rational “metahuman” individualistic hero, Mr. Terrific (Edi Gathegi, Eddie Willers in Atlas Shrugged Part One), the most interesting character besides Superman and Lois Lane. Gathegi steals scenes with his delivery, yet he conveys a seriousness that others lack. Luthor’s character can grate. The villainy’s not as enticing as the heroism. Though the actress suits the role, Rachel Brosnahan’s lines as Lois Lane can fall flat, such as when she laments a “profit factor” as if profit’s wrong or bad. An intelligent reporter in love with a hero would be likely to know that profit’s human and good.

What also grates is the pace and undercutting of anything serious with something cynical in those trivial, insider references young people obsess over at the expense of appreciating the beauty and meaning of life, America and the movies. You get used to it. Particularly if you’ve endured those god-awful Marvel movies. They’re convoluted and stale and younger audiences lap it up with the attention span of an interstitial but comeuppance comes when a primitive people start chanting “Superman!” which comes in defiance of what today’s youths are indoctrinated to accept about primitive people as superior for being primitive. This is because it’s not the Americans crying out for a hero. It’s primitive foreigners pleading for a civilized rescuer from the West.

Even small scenes, such as that blue, yellow and red-colored and caped hero against the dust and rubble of a city in darkness—Black Tuesday, Texas floods, Los Angeles in wildfire and other tunnel scene scenarios come to mind—evoke powerful emotion. Superman taps the sense of a country—the United States of America, despite its name being purged, sidelined and miniaturized—including invasion of a country. It’s also a tale of number-crunching, code-punching technocrats worshipping those disgusting cronies of “government authority.” It’s the anti-hero versus the hero. The statist is vanquished. The hero rises up—and with a woman of reason who’s his equal (who proves capable of being his savior) as his reward. Too many quips, too many micro-plots, too much villain and too little Man of Steel can’t stop Superman from making a fresh start which honors a heroic spirit.

Earlier this year, after witnessing a historic supersonic jet flight created by a friend who founded an aviation company, I asked “Who is Superman?” In the essay, I proposed that you are—that my friend is—that I am—that every man of ability can be. Seeing this mythical hero on screen again reinforces my contention that this is true.