Movies: “Lover of Men” and “Am I Racist?”

Propagandistic Abraham Lincoln and racism documentaries lack credibility

Recently, I saw two documentaries at local movie theaters. I was invited to attend the premiere of a new, independent documentary about Abraham Lincoln by one of the film’s producers. This was a festive affair in Century City. I was also invited to attend a screening of conservative filmmaker and Daily Wire contributor Matt Walsh’s new movie about racism.

For clarity, unless I know an artist on cast or crew, I strictly see movies from which I have at least some reason to think I can gain value. In the case of Lover of Men: The Untold History of Abraham Lincoln, I was drawn by the theory that Lincoln may have had homosexual tendencies, as evidenced by his correspondence with Joshua Speed, first presented as I recall years ago with what I regarded, then and now, as having some legitimacy. I wanted to know more about this theory. I was similarly attracted to Walsh’s movie (Am I Racist?) because I know that he went undercover and claims to have obtained permission from leftist academic intellectuals, such as Robin D’Angelo, the White Fragility author and scholar who prejudges white people as inherently racist.

In both cases, I was curious to watch the filmmakers attempt to prove points and make their cases, i.e., that Lincoln may have had sex and romantic love with men and that supposed anti-racists on the left are a fraud. In both cases, I admit that I’m predisposed to conclude that both claims are probably, almost certainly, true. I still think this; that Lincoln was probably gay or in love with a man (or men) and that professed anti-racists on the left project their irrationalism, including racism.

Neither film is good. Neither film really proves a point. Neither film really makes a strong point, let alone a cohesive case. Both movies are propaganda—leftist and conservative propaganda—and are examples of bad propaganda. Both movies also have merit. Intentionally or not, and I’m inclined to think it’s deliberate, both Lover of Men and Am I Racist? do not seek to elucidate and inform an audience; they aim to grab attention and then confuse and derail one’s logic. Both movies are, in this sense, anti-conceptual. On their own terms, neither film persuades anyone of anything serious. They amount to displays that show and tell and fall flat.

Accordingly, this double feature review of both movies, weighted toward an examination of the more serious film (and more deserving of the term documentary), Lover of Men, focuses on essential points.

Am I Racist?, like the pseudo-documentary Borat, is cynical. It’s about nothing. Walsh narrates, appears, acts, hams, poses, pretends to scrutinize and question and goes in disguise. Never does he appear to honestly scrutinize the opposing viewpoint—at least not with a depth of commitment or seriousness—that he’s lampooning. Though he’s not as showy and theatrical as satirists such as the late Rush Limbaugh or the late Andrew Breitbart, he’s also not as credible as independent conservative journalist Andy Ngo or others; Walsh’s Am I Racist? exists to entertain, not to educate.

For example, he does not define racism. Not once. He doesn’t come close to trying. Instead, he goes after (and under cover with) certain thinkers, mostly leftists, to show them up. In several cases, the leftist comes off as more, not less, decent than Walsh, who lies, deceives and misrepresents himself to those with whom he purports to meet under the pretense of making a movie. In fact, Walsh was making a film but not as an advocate of “diversity, equity and inclusion” (by the business acronym DEI, the leftist package deal religion) as he claims.

That’s fine on its terms but Walsh compounds the deceit by faking his name, identity, job and/or situational context for dramatic, not intellectual, purposes. For instance, he lies about his experiences. He also violates group terms and conditions and, though he pays his way, according to the film, compensating sham anti-racists with tens of thousands of dollars, he’s often rude, abrasive and disruptive. In short, Walsh in seeking to show up anti-racist frauds as frauds, gets in his own way.

In one segment, a group leader—whose premise is outrageous—comes off as more rational than Walsh. A film that makes this possible does more harm than good for understanding racism. In the D’Angelo setup, Walsh fakes and falsifies his own views to lure her into looking foolish and betraying her professed principles—which, to the degree one can make sense of her irrationalism, is the belief that white people are inferior—and, when prompted, she pays what she calls reparations and acts in accordance with her principles. Am I Racist? backfires like this over and over.

By the end of Am I Racist?, Walsh, who renounces a relative he refers to as “racist,” sits across from and goes along with the racist relative. This final shot suggests that sanctioning a racist is easier than and preferable to sanctioning a closeted racist masquerading as an anti-racist. Is it? Without a definition of racism, let alone providing a view of racism—let alone offering a proper alternative, i.e., individualism and capitalism—Walsh does worse than leave his film’s question unanswered; he implies that the answer (as it applies to him, seated at peace with a racist uncle) is Yes. As conservatives, who corrupted and ended the Tea Party movement, usually do, a good argument goes ignored (or evaded) while a horrific argument goes unchallenged and, badly, undeniably, gets reinforced.

Lover of Men: The Untold History of Abraham Lincoln

Like Am I Racist?, leftist Lover of Men’s flaws lie in its title. Unlike Matt Walsh’s cinematic exercise in caustic, conservative gotcha cynicism, it’s based on documentary evidence that’s sporadically presented. The film examines Lincoln's relationships with four men—centrally, Joshua Speed, who shared a bed with Lincoln for four years—including Billy Greene, with whom Lincoln shared a cot for 18 months, Elmer Ellsworth, an eccentric decorative soldier, and Lincoln's Civil War bodyguard David Derickson, who shared Lincoln’s White House bed while First Lady Mary Lincoln was away. Citing letters and correspondence, eyewitnesses and opinions from historians, Lover of Men, a title the movie doesn’t exactly substantiate, showcases claims suggesting Lincoln found companionship with men.

This starts off as compelling. The strongest case comes with the assertion that Messrs. Speed and Lincoln were in love. This is mitigated by constant re-enactment displays, without corresponding evidence, of mutual affection and romantic expressions between men. Dependent upon interpretation of limited circumstantial evidence, the movie’s credibility falters. With what filmmakers claim are never-before-seen letters and photographs, Lover of Men delves into Lincoln’s relationships with men, which ought to have been the movie’s main focus. Abe Lincoln’s customary signature to Joshua Speed, “yours forever,” supports the theory.

Instead, the writers and director drift into what they claim is a history of human sexuality, contrasting 21st and 19th century practices. This is unfortunate, because early, basic historical and biographical material, such as the Civil War being a “war of [slavery] abolition” (which it was), Lincoln migrating from Kentucky to Indiana to Illinois, his mother suddenly dying and his enjoyment of reading, is solid. Mixing facts with speculation about sexual practices dilutes the film’s strengths.

That Abe Lincoln did not like farming, hated his stepmother, thought girls were “too frivolous” and became suicidal over the extended absence from Mr. Speed, is backed and supported here. For example, the nation’s 16th and first Republican president wrote that he was the “most miserable man living” after being separated from Mr. Speed. He added: “I must die.” Lincoln’s visit to a slave plantation owned by Joshua Speed’s father—Abraham Lincoln’s longest firsthand exposure to slavery—ended when he left the property in apparent disgust on January 1, 1841.

What might’ve been an interesting transition from romantic love tragically subordinated to tradition—political, religious and cultural—to a civil war over slavery instead veers way off track. The filmmakers pontificate on what they describe as “queer history,” whatever the heck that’s supposed to be in the mania of acronymic sexual politics. Not every assertion in the detour is wrong, bad or without value—on eugenics, a pseudo-science the filmmakers decline to attribute to Democrats, such as Woodrow Wilson, and leftist religionists, Lover of Men rightly points out that fake science was a “new religion”—but it’s mostly arbitrary and poorly conceived.

Amid radical gay and transsexual activism and revisionism—historians and scholars as talking heads make way for a transsexual politician and an apparent man in a dress with five o’clock shadow and hoop earrings—Lover of Men deviates far from Abe Lincoln. From an exercise in proselytism for transsexual propaganda to the film’s ultimate point that so-called equal rights for transsexuals equate with the abolition of slavery—a preposterously unwarranted comparison—the film collapses into shrill, vacant political slogans. Marketing materials disclose that Lover of Men: The Untold History of Abraham Lincoln is partnered with a radical gay activist group (the Human Rights Campaign Fund) and discusses the prospect of authoritarians that “impose sexual values” on innocents.

With its left turn from exploring Lincoln’s history toward advocacy of “equality of opportunity” for transsexuals, Lover of Men imposes its sexual values on an audience that simply seeks to learn about one of America’s greatest presidents.

Carl Sandburg once wrote in his Lincoln biography of the assassinated president’s “streak of lavender,” a phrase the film asserts was cut by the author from later editions. Sandburg’s reference to the color violet was also removed by the author from an introduction. If this—with other facts, such as Lincoln’s bursting into tears at the mention of his deceased male companion’s name (Elmer Ellsworth, who was shot to death while taking down Confederate flags to honor President Lincoln, becoming the first casualty of America’s Civil War), is true, Lover of Men might’ve left it at that and let the audience observe and contemplate its facts and values.

President Lincoln apparently deeply loved at least two men—Speed and Ellsworth—and spent the night with Ellsworth’s corpse. Such a potentially poignant, powerful story of love between those of the same sex needs no adornment. Propaganda equating transsexualism with same (or opposite) sex romantic love trivializes true love.

The pattern, trend and tendency to smear and dishonor the detection and discovery of truth about facts and history unfortunately continues in movies—whether Michael Moore’s, Matt Walsh’s or films funded by radical gay leftists. If it feels like learning the truth is both laborious and tedious—and, in today’s propagandized media, it does—here’s the opportunity for the truly independent moviemaker to break out and create a movie with honesty. Today’s audiences need it now more than ever.

Related Articles and Links

Series Review: Jackie Robinson on PBS

This two-part documentary, originally shown five years ago on PBS, leaves gaps as it informs. A narrator sets forth facts of Jackie Robinson’s life and provides the context for the next few hours. Viewers learn essential information about Robinson, including batting averages, business deals and performance on the baseball field.

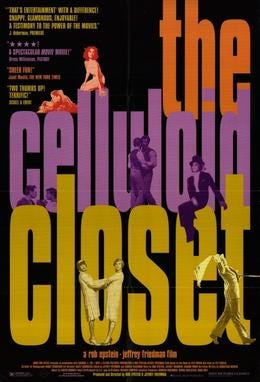

Movies: The Celluloid Closet

In 1995, a documentary about gays in movies debuted. The result, based upon a gay activist’s book of the same name, is The Celluloid Closet. The 102-minute film begins and ends with grainy film footage by Thomas Edison—the world’s first moviemaker—of two men dancing. The adaptation of the book, also a college-level course by its author, the late film historian Vito Russo, was funded by a variety of sources, including state subsidies, HBO and Hugh Hefner.

Series Review: Hemingway (PBS)

Billed on America’s state-sponsored television programming, Public Broadcasting System (PBS), as “a film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick”, the three-part Hemingway stuns, informs and stimulates. This is Burns’s best documentary. I learned more about the 20th century’s influential, suicidal and bestselling writer than I’d ever known.

Perhaps this should be under the heading of 'my taste' which obviously may not be for everyone, but I firmly believe that in order to be effective, documentaries (which for the record I have not written or worked on) must reveal some essential truth. Yes, if someone is telling lies and/or committing fraud, it's good that such activity is exposed for what it is. But if I were going to be a documentarian, I would want to use that act of exposing as a springboard to revealing essential truths. Challenging? Of course, but so is making any good movie.

Gay or not, he was one of the greatest of the Presidents.