It’s easy to gloss over that this 1993 movie’s title derives from a children’s nursery rhyme. The rhyme’s a plain observation about a bridge in collapse. Falling Down is that simple, too. Somehow, this tale of structural erosion becomes a moving portrayal of America’s most marginalized, persecuted individual—the productive one—with sharp social commentary. This is possibly the late Joel Schumacher’s finest film.

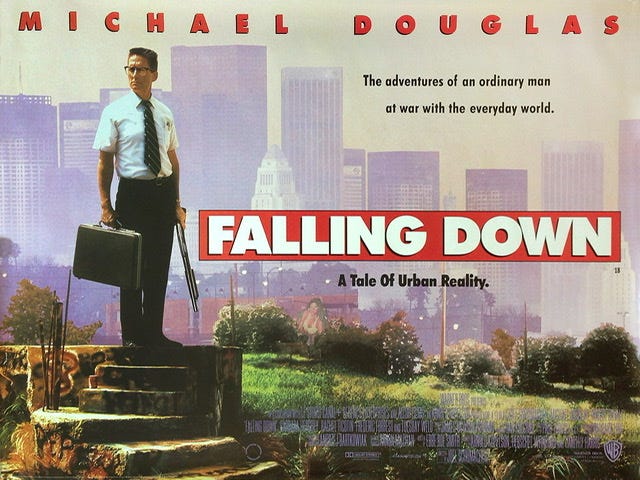

The depiction of early Nineties Los Angeles is as eerily predictive as Atlas Shrugged. The movie, stalled in production by what at the time were America’s worst riots (LA in 1992), advertised as a tale of one man’s undoing—a U.S. defense engineer played by Michael Douglas in one of his better performances—Falling Down contrasts the Douglas character’s breakdown with the retirement of a cop portrayed by Robert Duvall. Both are outcasts. Both are older white men targeted and attacked, dismissed, belittled, humiliated and emasculated for being older white men. One responds by bein…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Autonomia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.