Movies: Anatomy of a Fall

How to pick yourself up and get closer to perfection by picking yourself apart

Anatomy of a Fall gets me thinking. This is an all-encompassing motion picture. Its characters, plot and theme stimulate, stir and soothe all at once in waves. At times, it’s an edge-of-the-seat, intellectual thriller. The movie’s sharp, visceral, emotional, psychological and extremely challenging. It’s likely to get you thinking, too.

Allow me to explain why. The film’s allure begins with the eyes of a beautiful dog. He’s affectionately known as Snoop, which I take to be short for Snoopy, but Snoop, as it is, is a fine name for a dog you’ll want to watch for important clues because, like a knowing detective, Snoop snoops, sees everything and knows more than he can reveal.

The fall of a mysterious man is merely a catalyst and primary mystery. Deeper mysteries abound. Whether a man’s fall is murder or suicide dominates Anatomy of a Fall, however, the stakes are higher than criminal justice—the matter at hand in this masterful psychological puzzle—and involve one’s highest values and life’s greatest rewards. I don’t mean to be cryptic.

Spoken with several languages, including English, and with English subtitles, Anatomy of a Fall puts thoughts, ideas and actions into play over and over for the audience to observe, absorb and contemplate. At two and a half hours, it’s a longer film, moving fast, sometimes at breakneck speed, while allowing you to think twice, reconsider, and reach a conclusion. Mind your judgment. But mind whether you make a judgment; the movie challenges, tests and is designed to mirror you. You—not merely the main character, a woman who’s a writer, wife and mother—are on trial.

Evoking the bitterness of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the fragility and eerieness of children-themed pictures such as Silent Fall, The Sixth Sense and Kramer Vs. Kramer (with a touch of The Bad Seed) and the psycho-philosophical precision of The Lives of Others, this 2023 movie measures the whole scope of life within 160 minutes. For example, mother-son, wife-husband and client-attorney—as well as other—bonds get detailed dramatization.

So does the relationship of an artist to his work of art, whether writing a novel or playing a piece of music. Indeed, like The Lives of Others (which is a cinematic statement against altruism), Anatomy of a Fall airs the anatomy of making works of both art and life in progress—in writing, marriage, parenting, defending and, especially, practicing self-care—in what can best be described as a poem depicting how to pick yourself up and get closer to perfection by picking yourself apart.

The evidence is in every other scene of this mountain chalet-based movie. You decide what matters. Whether a mother steps out into the cold to make a telephone call, or a wife cries while watching a silent video clip of her late husband or a writer drives along the icy, curving roads of the French Alps, each action, expression and reaction adds up to whatever you make of it.

“I don’t believe it,” the woman’s lawyer says early in the picture after presenting a mock defense scenario recreating the husband’s hypothetical suicide. That the married couple are both writers is a factor. That the couple’s only child is a son who’s a prodigy matters. That he’s had an accident becomes an issue. Everything’s at issue, yet some points matter more than others and it’s up to you to decide.

“I don’t give a f*** about reality,” someone says at one point. In a subtle film about the deeply rooted roles of an unfinished novel, sexuality and sexual orientation, so-called disability, earned and unearned guilt, self-pity, place and the power of the English language in the pursuit of one’s happiness—or the death spiral of one’s final acts of desperation—the simplicity of its clues may surprise, delight and horrify you. Anatomy of a Murder, Otto Preminger’s saucy 1959 courtroom drama starring James Stewart, inevitably invites comparison. Here, director Justine Triet, co-writing the script with her romantic partner Arthur Harari, goes for moral clarity over moral ambiguity.

“The recording is not reality,” someone dares to object to today’s prevalent religious faith, technology, in one of the movie’s most powerful lines. Taking place near southeastern France’s mid-sized mountain city of Grenoble, the screenwriting revolves various themes and possibilities always to orient and elucidate, never to smear, blur or confound. Anatomy of a Fall has a way of dramatizing essentials in alternately gouging and smoothing brushstrokes.

“I’ve already been hurt,” the child, named Daniel, points out to an adult who’s claiming to act for the sake of his protection in a crucial and relevant clue. Echoing Hans Christian Andersen’s fable about The Emperor’s New Clothes, the boy’s boyhood growth, innocence and intelligence slowly refract as the fall’s facts become clear. As it does, the fallen’s weakness or strength, cowardice and shame or confidence and courage—centrally, philosophy—rises in proportionate significance with every frame.

“How do you prove that?” A suspect rhetorically asks about being in love with a soulmate. A climactic feud—the true meaning of jurisprudence—the value of asking why?—and another crucial drive through the winding roads of the Alps begin to let you learn whether your suppositions may be on the proper path.

Anatomy of a Fall showcases in penetrating scenes life’s layers of complexity in communication, life and romantic love. It’s a tour-de-force movie about the exhaustive effort of being rational in an irrational culture in which the dog knows more than the ones who ought to know better. By the final scene, which captures the simple truth about being alone, you’ll know more about your own philosophy and, which can matter more, you’ll better grasp whether and why you’re wrong or right.

Through a unique and piercing mirroring of your own bias, subjectivism or tendency to be taken in by prejudice, sexism and, specifically, rationalism or cynicism, this extraordinary movie breaks down the facts of life. Anatomy of a Fall dramatizes marriage, childhood, parenting, domesticity, journalism and the judiciary, unrequited love, introspection and extrospection, artistry and sophistry—and, at its core, the noble and solitary struggle to go by reason and begin to replenish one’s love of life to supply to oneself the requisite energy needed to go on.

Related Links and Articles

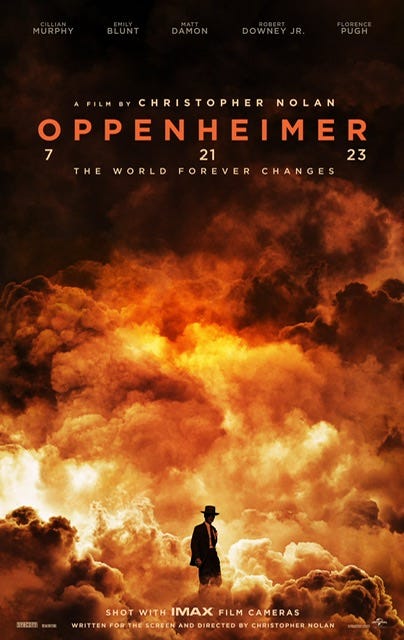

Movies: Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer—the film for which Nolan left Warner Bros.—overloads the mind, numbs the senses and flattens the characters. In short, it implodes.

Movies: Casablanca

Do you know Casablanca? If so, have you seen the movie in a theater? What do you think it means? I first saw this 1942 Warner Bros. movie on television. Later, I watched Casablanca on VHS, then on DVD and again via streaming. Years later, I watched Casablanca

Podcast: “The Color Purple” (2023)

Scott Holleran reviews the 2023 motion picture musical version of the novel.

Movies: Belfast

Kenneth Branagh’s fable in black, white and gold splashed with deliberate scenes in color couldn’t be more relevant and timely. The story is a contrived slice of life. But Branagh, whose brilliant career spans Shakespeare’s classics, Disney’s Cinderella

Movies: Equalizer 3

Strictly in the context of today’s motion picture quality, which is getting bleaker, this sequel, starring Denzel Washington, excels. It’s emotionally potent. It stimulates the senses and, to a lesser extent, stirs one’s thoughts. The second sequel in the movie franchise based on Michael Sloan’s and Richard Lindheim’s original CBS show makes you scared…

Well, Scott, you've done it again. I now feel I must see "Anatomy." Before this review, I had no such intentions!