For an interesting comedy to ease yourself into the new year, you can appreciate the disarming manner of Elaine May’s A New Leaf. It’s a light, enjoyable tonic with which to toast to making fresh starts of what’s gone stale. Comedienne Elaine May, partner to Mike Nichols, sought to adapt Jack Ritchie's murder-themed short story, “The Green Heart,” for film. May reportedly commented that: “Halfway through it, you understood that the guy who was going to murder the woman really loved her and didn't know it…you read the story and thought, ‘Oh, he's not going to know it in time.’”

Who better to portray murderous suitor Henry Graham than homely character actor Walter Matthau—who’d been rising in stardom after playing sportswriting slob Oscar Madison in Neil Simon’s The Odd Couple—in 1971? Establishing at the outset that heavy debtor and disinherited Henry’s an insecure, shallow secondhander who’s oblivious to his own worth—and to the meaning of money—A New Leaf provides ample background with James Coco’s sadistic uncle. As you prepare to hate Matthau’s cavalier Henry, Coco’s cruel relative gives a glimpse of the family as tyranny.

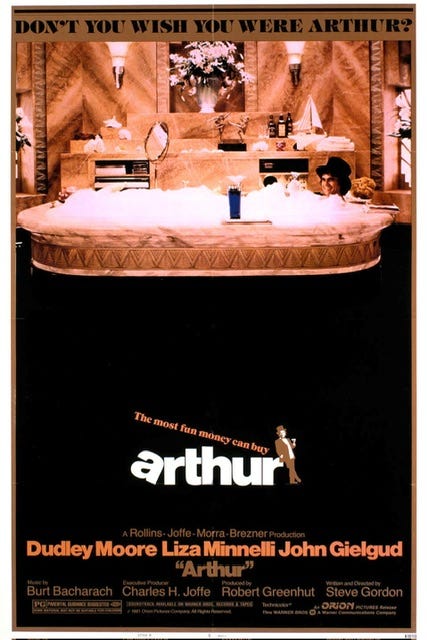

You realize how Henry ended up this way. His butler, giving two weeks notice, framing the uncle’s preemptive, punitive deadline to find a wealthy woman to marry within a couple of weeks, is the only direct and honest person in Henry’s life. This film’s an entertaining, layered precursor to Arthur co-starring Dudley Moore and Liza Minnelli. Elaine May, who wrote and directed the refined little movie, portrays Henry’s target: a wealthy female botanist with no heirs named Henrietta Lowell.

Henry courts clumsy Henrietta with a rebellious streak, which she finds endearing. Awkward Henrietta fumbles, losing her glasses, spilling tea and mumbling like a stereotypical scientist. Henry takes genuine interest in her work in spite of himself. What’s more evident is that Henrietta takes genuine interest in the whole man who is Henry Graham. Once they commit, Henry plots to be rid of Henrietta to inherit her money; she finds the good in him. A New Leaf hints that she may be hip to his intent.

Henrietta encourages Henry to put his college degree to work. As he becomes efficacious and slightly more virtuous, she becomes empowered and more ambitious, taking chances on herself. He becomes househusband, managing domestic affairs and keeping books—with the butler’s help, detecting property theft and embezzlement (look for a younger, thinner Doris Roberts from Remington Steele and Everybody Loves Raymond)—as Henrietta becomes the head of the household, focusing on botany, including field trips and A New Leaf’s theme, discovery. Henry discovers himself.

If this comes off as standard feminist fare, it isn’t. Thanks to Miss May, an intellectual whose career stalled and, later, was stifled, A New Leaf grows in the unearthing of an insular, hero-worshipping woman of reason who wants to love and be seen, noticed and loved as she is. Henrietta knows she deserves to meet her match. When she does, she knows she also deserves to be rescued from him at his worst, too, which makes the affair both uniquely neurotic and romantic—aligned with making new cheers and resolving to be one’s best or, at least, better than before.

Related Articles and Links

Liza Minnelli Movies

Within this silly 1981 romantic comedy, Arthur, a star vehicle for comedian Dudley Moore, lies the simple wisdom of living within your means, finding true love by aligning chosen values with another person and grasping the meaning of money. Arthur’s not as fancy as all that. It is innocuously humorous and gay.

Liza Minnelli Movies

This sequel to Arthur, which takes place four years after the original, features a return of the original cast, including comedian Dudley Moore and co-star Liza Minnelli. Arthur 2: On the Rocks, a middling title from when sequels were driven by numbers and cliched subtitles, also features pre-

Clint Eastwood Movies

Juror Number Two, directed by Clint Eastwood, ends with an answer to how it begins. It’s a short, quiet scene which mirrors the foreshadow. This movie, the best I’ve seen (as of now, including the excellent Conclave) in 2024, surprises, stimulates and ascertains with flair and re-finishing. The ending lets the audience be the jury, proving again that actor and director Eastwood (