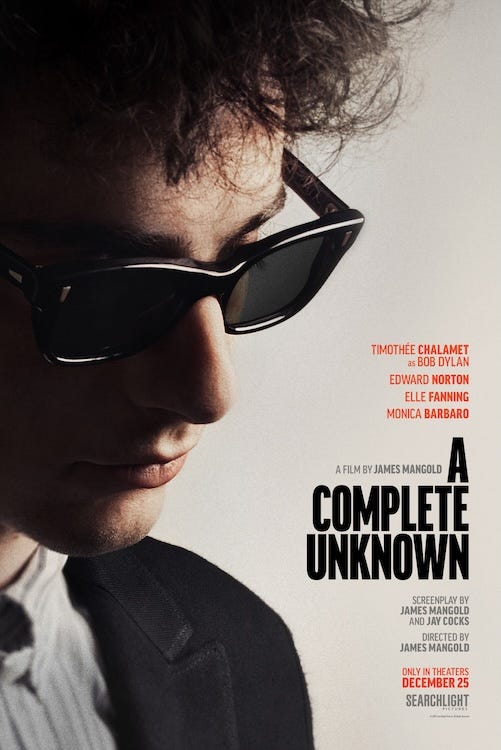

Movies: A Complete Unknown

The Bob Dylan biography dramatizes altruism versus egoism in politics, life and art

The torture of being an artist, as against being the tortured artist, defines what may be director James Mangold’s best picture. The director of Walk the Line, a commercially successful biography of Johnny Cash, directed a Western remake years ago. None of his movies particularly interest or impress me for the record. Walk the Line made an impact for personal reasons but it’s not a great movie. A Complete Unknown is better.

The skill lies in its title. If you’re an artist—and if you love or have loved an artist—you know the anguish of what it costs to create. Creating is an extremely solitary endeavor. Learning how to live with, let alone love, another person while seeking to make a living as a creator can be elusive. At times, it seems impossible. A residual sense of isolation from the effort can be excruciating. Yet you try. That singer-songwriter Bob Dylan lyrically self-describes as the movie’s title and, later, copes with being known and loved is why Mangold’s movie is likely to endure.

Leading actor Timothee Chalamet as Bob Dylan under Mangold’s direction with screenwriting by Mangold and Time magazine’s Jay Cocks admirably performs. The introversion, mumbling, nasality and, most pointedly, the sense of purpose—each are tapped by his performance. A Complete Unknown is sleepy, somber and earnest. It tracks the years of the nation’s climactic cultural drift into total despair, from 1961, when darkness clearly loomed, through the end of that horrible decade. Framed within the life and career of an American Midwesterner and a Jew, A Complete Unknown puts several pressing questions to the audience.

Among these: do you exist for the sake of others? Can you succeed on your own terms? Can you glide on a trend without becoming lost in a mob? These are timeless questions which, whether you know and value various mysteries of music—hip-hop, country, rap, classical, rock ‘n’ roll, and, particularly, in this film, folk—must be answered by rational man—most urgently by anyone calling himself an artist. Bob Dylan is an artist. Steve Jobs knew this; so did many others. A Complete Unknown skims the surface of Dylan’s work and life, which, in full disclosure, I barely know.

I don’t need to know in order to judge this film as good. From Dylan’s earliest days coming to New York City from the cold north of Minnesota, only to be sent to New Jersey to play a song for Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger (Edward Norton) to the epic self-realization that he, too, could end up dying before he could be born, this is a movie about facing the challenge of being born too soon.

“How does it feel?!?” It’s too easy to mock and minimize Dylan’s most famous question in today’s cultural context. It’s more challenging to consider what a serious quest this question posed when Bob Dylan sang it, throwing down with defiance, the sum total of what he had learned like a gauntlet against the world. Single-handedly, he put folk music, with its anti-music, anti-art, anti-life ethos, in its proper place. A Complete Unknown dramatizes this with cutting clarity.

The culture of America seeps into every other scene with a reward for the one who knows. The insidious U.S. intervention in Southeast Asia under the Kennedy administration—President Kennedy fathered the Vietnam War—Kennedy’s 1963 assassination in Dallas, Texas, the civil rights march on Washington, the assassination of Malcolm X, the Beatles—the writers weave these historic events into the story of an artist who creates for his own sake. Early in the picture, “the government” is cast as an ominous offscreen presence. It’s a telling cue, which eloquently dovetails into the film’s theme that being an artist of ability necessitates being subversive. The writers use this word, too.

Bob Dylan comes to what was once America’s greatest city to “catch a spark,” which, for me, evokes a profound thought from Ayn Rand about never letting the spark go out. As he writes, sings and records songs, his home becomes a mess only to those who misunderstand the trade-off of making art. Journals, books, crutches—his physical possessions and material things—are everywhere in his home. An invasion of Dylan’s privacy and property foreshadows a deeper intrusion to come. One of the film’s tragic heroes is Johnny Cash who reaches out to Bob Dylan. Bob Dylan reaches back. They forge a bond but not before Dylan reads a letter from the troubled country singer while sitting alone in a New York City park.

Solitude is the motif. Dylan connects and hooks up. A fear-driven, political songwriter and songbird who follows the herd, Joan Baez, pairs with him in a telling depiction. Baez, a narcissist who drains life from him—kicking Dylan when he’s down—embodies the solitary artist’s antithesis: activist as fundamentally anti-social.

Writing poetry for politics ultimately causes the breach between Dylan and the folk music movement which, like Black Lives Matter and Me, Too movements, becomes a dogmatic disaster, destroying love, civilization and art. Through it all, Dylan enlists an ordinary young woman in love, portrayed by Elle Fanning in one of her best performances. Though their story is wrenching, you want them to be together. But she’s sweet and sensitive and he’s harsh and hardened. Whether they align deepens and embosses A Complete Unknown. This is Mangold’s tribute to Hollywood and it’s more compelling than the Forties melodrama he echoes here.

Consider seeing A Complete Unknown alone. Brace for its intimacy. Forgive the pace. I recommend seeing A Complete Unknown at a time of day and in a place with reason to think the audience will show respect. During my Christmas day showing, a young woman with an older companion ate popcorn, crunching and chewing one kernel at a time with her mouth open for the duration of the film, which thoughtfully integrates Bob Dylan’s songs and yields its most affecting scenes.

Perhaps she was ignorant or didn’t want to be there. Judging by this film, based on a book, Bob Dylan wants to be here, expressing this in music which shows evolution and progress. Dylan declines to be pigeonholed into Stalinist propaganda for the New Left. Dylan does so by mining playfulness in an instrument from a street vendor. He pursues his goal day by day, night by night, sucking on more cigarettes as he makes money, succeeds and tries to be true as he strives to become known.

This is a lifelong effort. Finally, in a comment to the woman for whom he’s the love of her life about what it’s like to be Bob Dylan in the late 1960s, he delivers one of Hollywood’s most devastating lines. It’s an explanation about the culture—a commentary on encounters with his fans; he admits that, when they praise his tunes, the accolades are cloaked in an unspoken complaint born of pure envy. Layered into this is the unnamed essence of what Dylan comes to realize is the most deadly infection of all—altruism. One he’d hoped could’ve known better, Joan Baez, pleads and ponders about pleasing others, which taps the folk movement-New Left premise.

Bob Dylan, to his credit, and this may be why he earned the respect of America’s most ingenious, modern creator, Steve Jobs, rejects the status quo and establishment—appropriately at a festival in Puritanical New England, the perfect symbol of folk music’s bland traditionalism. This is the meaning of A Complete Unknown—portrayal of man in reclamation of his soul.

It comes in a brief, embittered, pin-drop performance of the song which practically raps the movie’s title. See this, listen to this and watch to bear witness to—and learn from—Bob Dylan remaking life, with or without romantic love. A Complete Unknown tests your knowledge, confidence and self-esteem if you’re alert and paying attention and it can move and probe you where you’ve been sedentary or wounded. It depicts the resolve to know what it means to be known, if unloved, and to express in music exactly how does it feel.

Related Articles

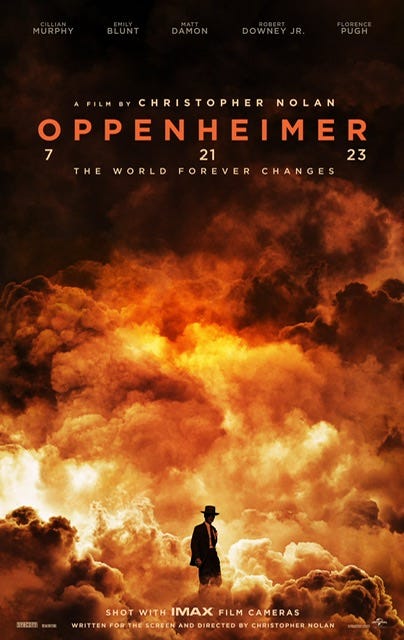

Movies: Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer—the film for which Nolan left Warner Bros.—overloads the mind, numbs the senses and flattens the characters. In short, it implodes.

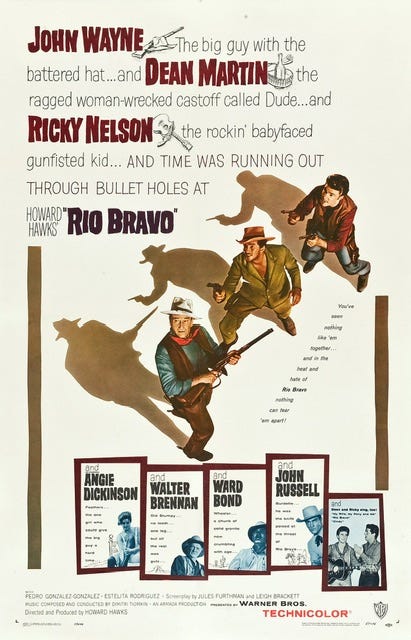

Movies: Rio Bravo

Watching Rio Bravo is time well spent. The classic 1959 Western by director Howard Hawks is deceptive in its goodness, so that it’s easy to underestimate the value. Many of today’s Americans take John Wayne’s sensibility for granted or they hold it in contempt, if they know of him. In

https://open.substack.com/pub/johnnogowski/p/dylan-destroyed-one-world-started?r=7pf7u&utm_medium=ios