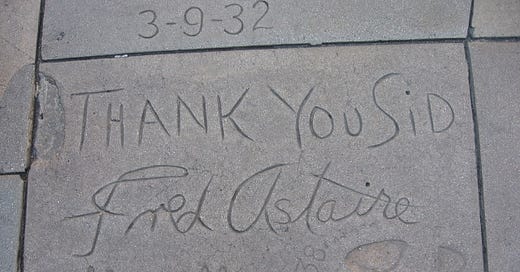

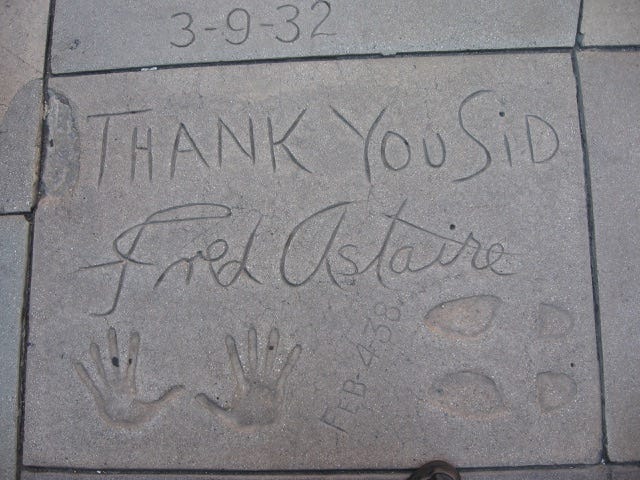

Just Deserts: Celebrate Fred Astaire

Today’s the dancer, actor, singer and movie star’s birthday in 1899

Day after day goes by, often with some meaningless, artificial or vacant cause being thrust by the shrillest voices in government and media—without the ablest persons getting just desserts. This is why I celebrate Fred Astaire’s birthday. The greatest dancer in the previous century’s newest art, the movies, deserves more than mere remembrance. Fred Astaire, especially Fred Astaire, ought to be celebrated.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Autonomia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.