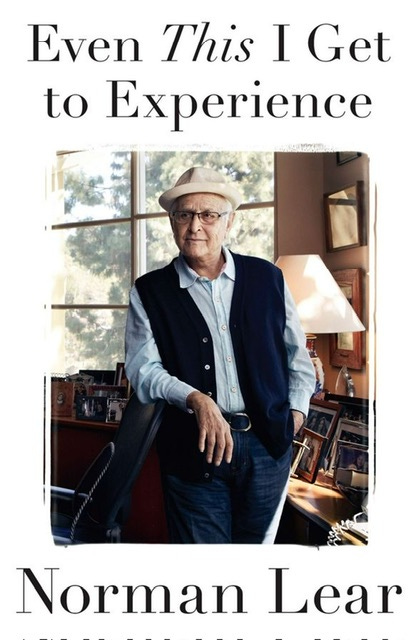

Even This I Get to Experience (Penguin Press, 2014) by Norman Lear, who died this week at the age of 101, moved me when I read it a few years ago. In the aftermath of his death, I re-read my margin notes. Because his is a remarkable career in television—he was a true freethinker—I want to pay tribute to a creator. I wrote this review. (For additional, personal thoughts, including meeting Mr. Lear, listen to my forthcoming podcast for the paid subscriber).

Norman Lear, whose work you probably know (which is probably why you’re reading this), starts his memoir with characteristic directness, depth and humor. But know that his is a jarring and honest account of his life. The man who created indelibly American TV shows revolving around brash characters such as J.J. Evans, Maude Findlay, Ann Romano, Archie Bunker and George Jefferson was an abandoned child with a sensitive soul. His sense of humor displayed realism—as he puts it: “we made comedy safe for reality”—and his brand was bawdy and loud, not restrained. But the comedic writer who’d worked in a “well-known burlesque house, featuring the most celebrated strippers of the day, along with the bawdiest comics” knew, accepted and understood—and insisted upon—dramatizing the tragic truths that forge character, not just jokes. The stories of Lear’s life made me appreciate his humor even more.

And his sense of humor is hilarious. Lear writes:

The younger kids couldn’t get enough of one particular story about a little girl who wakes up in the middle of the night with an itch in her bellybutton, finds a tiny silver screw in there, goes through all kinds of shenanigans before coming across a tiny silver screwdriver with which she is finally able to remove the tiny silver screw, then looks behind her and sees her little ass fall off.”

Before he was a master of TV’s comedy, he dabbled in motion pictures, even Broadway, and, before that, he pursued his passion in business. In Even This I Get to Experience, he writes about having the startup blues. Also, the perils of parenthood (“I was spectacularly unready to become a father.”) It’s clear from his candor that the man whose Ms. Romano stayed up all night to finish a project, whose Archie drove a taxi cab, whose George Jefferson hustled to make his dry cleaning stores profitable was always extremely productive.

He writes:

There were three other factories involved in the hot plate process — the frames were painted in Meriden, the switches made in Waterbury, and the nameplates made in Bridgeport. There was a lot of hauling to be done, and there were some weeks when our deal with the trucker lapsed and I did the trucking.”

Eventually, he came to California, where he discovered superior culture—not an admission most successful artists are bound to make, yet Californians know this is true—yet he does this without sugarcoating Hollywood scum, lamenting at one point that criticism of his TV comedies mostly “… came from establishment professionals, the people who run research and focus groups and are paid by the media and academia to tell us at any given hour who we are and what we are thinking.”

Even so, especially given the book’s title and italic, he delivers his raunchy humor. It’s not my favorite type of comedy, but Lear pulls it off as a part of his development and as a way of contextualizing today’s culture and comedy, baldly recalling the time he came across Jerry Lewis—“the irrepressible man-boy”—“alone on the sofa, with an erection, with a deliberately placed birthday candle, singing ‘Happy Birthday’ to himself.” Norman Lear writes: “Go forget that!”

Even This I Get to Experience includes pages of photographs between the stories of his adventures on Broadway, in motion pictures, and on television producing Good Times, All in the Family, One Day at a Time and The Jeffersons, among other TV programs. He adds: “Not bad for a little Jew from Hartford.”

Not at all—as the accolades come in after his death—and the liberal who championed the First Amendment in his political activism notes that he and his fellow Hollywood colleagues were “far more in love with America, and far more connected to the idea of America than we are now.” When one leftist attacked his situational, character-driven shows, Lear writes: “My response: ‘I am 22 years your junior, Madam, and meaning you no disrespect, if you have not known bigots of different stripes and attitudes, and to varying degrees, we are obviously aging in different wine cellars.”

Lear’s most notorious character—a complicated, beloved and redeemable bigot named Bunker—gets one of Lear’s most subtle and eloquent (and pre-Trump) reviews:

Looking back at it, I think Archie‘s primary identity as an American bigot was much overemphasized, because that quality had never before been given to the lead character in an American TV series. But the show dealt with so many other things. Yes, if he was watching a black athlete on television, he’d make an offhand, bigoted remark, and [hippie leftist son-in-law] Mike [Stivic, aka “Meathead”, who lived with his parents in law] would call him out on it. But the episode in which that exchange occurred might have been about Archie losing his job and worrying about how he was going to support his family. While a line or two could reflect Archie’s bigotry, the story itself was likely to be a comment on the economics of that moment, and the middle class struggle to get by.”

Lear also skewers religious people. Writing about his terrifying firsthand at-home experience with terrorism, he recalls that “the words “JEW-HATER—NAZI SYMPATHIZER” had been printed in large red letters across our white front gate. What the Dunnes [neighbors Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne] didn’t know was that a dead pig had been tossed over the fence and lay in our blood-splotched driveway. And it wasn’t paint that those hateful red words across our gate were inscribed with. This was the work of the Jewish Defense League, a vigilante styled group started by a rabbi, Meir Kahane.”

Lear tethers everything, including the year his groundbreaking show about a single, divorced mother of two teen-age daughters debuted, to reality, noting that, in 1975, the industry applied what’s known as the Primetime Censorship Rule. Lear’s best moment of standing on principle comes against a network suit known as Fred Silverman, the TV executive who killed Ayn Rand’s miniseries for Atlas Shrugged over money. Recounting his own business with the executive, Norman Lear remembers that “Fred Silverman was doing what his position called for. The network wanted the pilot—and now! As its owner, I said, I was well within my rights to keep it. But it was CBS who ordered it and had every right to see it, Fred said. My response: not until they agreed to pay for what they ordered. A day later, they agreed.”

I learned more about Norman Lear and his works in Even This I Get to Experience than I did from all the press and publicity that he generated over 30 years: that he recalled without hatred or hostility his fan, Rush Limbaugh. That he saw the musical Les Misérables four times. That Lear liked dealing with businessmen, including Home Depot president and CEO Bob Nardelli. That one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence—which Norman Lear revered—was John Witherspoon, a great-great uncle of Reese Witherspoon, whom he persuaded to “film an introductory welcome to the [free speech] exhibit and the document.” That his heroes include leftist talk radio host Thom Hartmann as well as Clark Gable. That animated character Eric Cartman was conceived as “an eight-year-old Archie Bunker”. That he appreciated The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers. That “of all the characters I’ve created in a cast, the one who resembles me most is Maude.”

I also read his thoughts on Michael Jackson, Robin Williams, Barry Goldwater, Maya Angelou, Johnny Carson—all of whom he liked and wrote about with warmth. I learned about comedienne Martha Raye’s demise at the hands of her husband. That Lear’s politics can be awful—he “proposes a new cabinet post, a minister of ethics,” expresses misplaced affection for President Kennedy and urges Americans “to understand the degree of the love and trust we of the middle class had for Franklin Roosevelt. He filled the singularly most important role I feel we need from our president. He was a father to us.”

Crucially, Norman Lear understands and reveres America as a nation based on rights. When he celebrated the Declaration of Independence—a writer celebrating one of the modern world’s truly greatest written works—he observes the document with honor: “Dated: July 4, 1776. ‘My God, I thought, it took months to get all the framers to sign the handwritten Declaration that I’d seen on visits to the Library of Congress. This copy, printed within hours of its ratification, is my country’s birth certificate.”

Of course, he recalls behind the scenes action on those famous TV shows. He also writes about lesser known works such as Palmerstown USA and “the nihilistic edge to Mary Hartman,” as James Wolcott described Lear’s strange, syndicated show in The Village Voice. A particularly insightful comment comes when Norman Lear remembers the literary impetus behind the long-running CBS show One Day at a Time: “What happens to Ibsen’s Nora after she leaves the doll’s house?”

TV anecdotes include First Lady Betty Ford “who would write to me whenever she missed an episode—long before the DVD and DVR—” and a forerunner to NBC’s Family Ties and ABC’s Soap, a politically themed comedy about a liberal-conservative romantic couple co-starring Richard Crenna and Bernadette Peters called All’s Fair. Lear recalls that the same TV network that cancelled All’s Fair dropped his Apple Pie “because it only drew 22 million viewers after two episodes.” He points out that “a Top Ten show today can draw less than half that [audience].”

The failed businessman turned phenomenally successful TV creator, writer and producer also explicitly injects his own mixed ethics when he writes that “after we sold [his company] Embassy, I set up the Lear family trust with a donation of $30 million. If you think that generous of me, I want you to know that I view it as equally selfish.” Despite Lear’s mixed and, I would argue, misguided and/or mistaken admiration for paternalistic-fascist presidents Roosevelt and Kennedy, his grasp of today’s political crisis—and this book was published nearly 10 years ago—excels:

Not once in all of the [2012 presidential] debates that culminated with Mitt Romney nomination for president did any candidate mention the five star general who commanded our troops to victory in World War II and went onto a two-term presidency of these United States, Dwight David Eisenhower. Maybe it’s just my loyalty to the ultimate World War II commander showing, but I can’t help but wonder if the denial of General Eisenhower by his [Republican] party has anything to do with the words he spoke as he left office: ‘We must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military industrial complex.’ It was the Congressional military industrial complex as originally written. “Only an alert and knowledgeable citizen,’ [Eisenhower] continued, ‘can compel the proper mingling of the huge military and industrial machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.”

Here’s an example of Lear forewarning of the rise of religion in America’s matters of state as he quotes a preacher: “I hope I live to see the day when, as in the early days of our country, we won’t have any public schools,” said Reverend Falwell. “The churches will have taken them over, and Christians will be running them. What a happy day that will be!”

As he did with Eisenhower, Lear does not play partisan politics, expressing about President Ford that Jerry Ford “believed firmly that the government must not favor any one religion over others, and that each man’s love of God was unique to the individual…we left the Ford home, after a very pleasant chat, with the president’s agreement to cochair [Lear’s free speech defense campaign] I Love Liberty.”

Politics aside, like some of his best characters’ most memorable scenes, Norman Lear offers real life insights, too, in his Even This I Get to Experience. “Recently, I read of the ‘parallel play’ that occurs when several toddlers are seemingly at play together,” he writes at one point. “While all might be engaged in the same activity, they are actually each playing by themselves.”

In expressing what frankly strikes me as this memoir’s theme, the late Norman Lear wrote in this entertaining personal account that he proudly remembers his daughter Kate describing her dad as a man who “walks through life’s peaks and valleys with equal wonder.” Lear later admits: “I am a here and now person.”

Indeed he was, as this book and his legacy of shows—which I still watch in laughter with friends—demonstrates. Quoting Aristotle at the start of his book’s third part, Joyful Stress, elicits the profound thought that “happiness is the exercise of vital powers, along lines of excellence, in a life affording them scope.”

Capping everything happy, humorous and thoughtful about Norman Lear’s exceptional and influential life, the author with a knowing smile beneath an upturned brimmed hat—worn to focus his audience on his handsome and welcoming face—cuts to the essence of what makes his comedy endure: “The humor in life doesn’t stop when we are in tears, any more than it stops being serious when we are laughing. So we writers were in the game to elicit both.”

Book Review: Sailor and Fiddler: Reflections of a 100-Year-Old Author by Herman Wouk

This book—published in 2016 with a tantalizing title—gathers stories about authorship. They’re by and about Herman Wouk. If you don’t know who he is, you should. Wouk wrote Marjorie Morningstar, The Winds of War, War and Remembrance, Inside, Outside and

Book Review: If—: The Untold Story of Kipling’s American Years by Christopher Benfey

If this enticing, bestselling book doesn’t quite live up to its excellent introduction, and it doesn’t, it is not for lack of effort. Author Christopher Benfey is astute and intelligent about key parts of Rudyard Kipling’s life, including his years in America. I learned more about Kipling, America and literature than I knew before reading

Book Review: Danny the Champion of the World by Roald Dahl

Roald Dahl’s father-son story, Danny the Champion of the World, is enjoyably brisk. With good transitions, exposition and Dahl’s surprise-laden storytelling, the novel unspools a light criminal caper—with the son of a widower and apprentice to his dad’s business narrating the action.

Book Review: Apparently There Were Complaints

CBS-owned Simon & Schuster sent Autonomia an advance copy of the new memoir (on sale this month for $27) by actress Sharon Gless. I had met and interviewed the co-star of the CBS show Cagney & Lacey in 2015 at a San Fernando Valley diner. Gless first caught my attention as a stewardess in the first sequel to 1970’s blockbuster

WOW! What a review! I am getting the book post haste. Thank you, Scott.