Book Review: A Love Story: The Miniature Railroad and Village

Pittsburgh’s most celebrated miniature train village gets a colorful centennial history

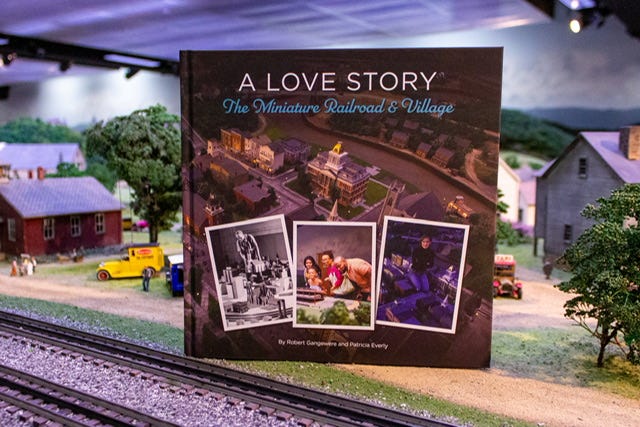

Published by the Carnegie Science Center in 2021, A Love Story: The Miniature Railroad and Village by Robert Gangewere and Patricia Everly is a compelling 102-page guide to Pittsburgh’s historically-themed diorama, which debuted during the early 20th century in a bachelor Army veteran’s basement.

Today, the Miniature Railroad and Village showcases certain Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania landmarks: Kaufmann’s downtown department store and Fallingwater, the house Frank Lloyd Wright designed and built for the Kaufmann department store founder, as well as Forbes Field, the original Primanti Bros. and, last Halloween, the stone chapel built in 1923 which was featured in George Romero’s gruesome and influential 1968 horror film, Night of the Living Dead.

The authors describe the story o…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Autonomia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.